It’s so sweet to be back, y’all.

Last weekend, the annual conference of the Kentucky World Language Association returned to Lexington, Kentucky. Last year, KWLA was my first conference since I paused blogging while I wrapped my mind around a diagnosis of MS. I embraced friends, sat quietly, absorbed the learning– but I didn’t present. This year, I presented a session for the first time since ACTFL ’19. I hope all attendees learned a lot as I had a blast publicly nerding out on language acquisition research and the brain. I promised those present that I would post my session here on the blog. So, here it is.

Where next?

You can catch me at ACTFL ’23 presenting more brain research in the session Teaching on TL Memory Lane Haylee Zieglerwith my amiga .

i+1 and the 5 C’s: Clarify, Amplify, Apply

In keeping with a conference theme focused on the ACTFL World Readiness Standards (known as the 5 C’s), my session attempted to help teachers see how the concept of i+1 could help them better prepare learners to meet the communication and comparisons standards, in particular. First, though, I knew that teachers don’t understand what i+1 is, so we needed to clarify before we could apply.

How we got here, and where we got confused

I’ve known for a long time that teachers don’t understand interlanguage. Years ago some fellow #langchat teachers and I had a conversation about it on Twitter and I was truly stunned at how much we’d made i+1 into what we wanted it to be. Those entrenched and successful in the Teaching with Comprehensible Input (TCI) / TPRS realm were convinced that the i was the input, and the +1 was input that was a little past the learner’s comprehension.

Don’t think that I had it all right, either, though. I did study i+1 in grad school, but then I became so enamored of TCI strategies and further brain research and thoughts like the Goldilocks corollary that I started talking about the +1 as being effort involved. (That is actually explicitly contrary to what is suggested in the linked article, by the way– but I think my view is more neurologically sound.) See, what’s called desirable difficulty in learning actually results in deeper learning and better memory encoding. So it made sense to me to start publicly advocating for what I call Goldilocks input. I’ll blog more about it soon, but basically, I advise teachers to strive for input that learners can understand but it takes effort to do so (not too hard, not too easy).

I digress. Because we all did. We all abandoned what i+1 actually meant. I knew it, but I didn’t know how deep it went. When I polled it on Twitter, 77% of respondents said the i stood for input. When I polled my session participants, 100% said it was input– and half the room had never heard of i+1 to begin with. My SLA research nerd heart was broken!

So let me take you back. The i stands for interlanguage. Some history will help:

- 1972– Larry Selinker publishes an article coining the word interlanguage. It refers to the systematic language a learner uses at any point on his/her individual journey. The article spurs a whole lot of helpful discussion and research.

- 1977– Stephen Krashen further upends the language acquisition field by proposing his five hypotheses, including the input hypothesis, which states that learners progress when they receive input at the level of i+1, where the i is their current state of interlanguage, and +1 is the next point in the journey.

- 1980’s– Blaine Ray’s TPRS methods resonate with teachers and spark a revolution that will become…

- 2000s– Teaching with Comprehensible Input (TCI) becomes a clarified set of strategies teachers use to deliver comprehensible input to learners.

To help teachers begin to see how this applies to lessons, we discussed a couple of clarifying principles.

Clarifying Principles

1. Interlanguage is about output.

We can’t take Selinker’s term and then make it about input. Furthermore, it’s a disservice to everyone who loves the input hypothesis and comprehensible input in general to suggest the +1 refers to anything that’s not comprehended. Learners don’t acquire language that is not comprehended. Period.

So, then, let’s go back to Selinker. In his definition he made it about their output: it’s “based on the observable output” and the “learner’s attempted production.”

To apply i+1, you must know that interlanguage describes output.

2. Effective lessons follow the interlanguage journey.

Here I had to insert some more language acquisition theory jargon, including processability theory, the inner syllabus, the structural syllabus, and the learnability problem. Simply stated, though, putting all of those together, you end up with this theory:

- The learner brain acquires language in a certain order (processability theory);

- that order works (inner/learner syllabus),

- and if you try to hijack it with your own plan (structural syllabus),

- the brain won’t learn what it’s not ready for (learnability problem).

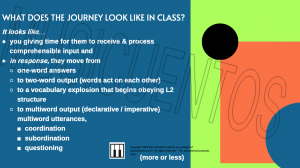

That brings up the key question to apply this in the classroom then, right? If effective lessons follow the interlanguage journey, how do I know what’s next on that journey? So, to start discussing that answer, I led participants through how second language acquisition researchers have proposed to draw the map, and then how researchers through first language acquisition have done it. You can see my suggested progression on slide 24 in the presentation, starting with one-word responses and moving through to questioning:

Designing i+1 Lessons

I offered the following advice for how to design lessons through an i+1 lens, focusing on the communication and comparisons standards:

- Pick something comprehensible, and make it comprehended.

- Ask for output you can reasonably expect here in the journey.

Expectembrace the errors that naturally come.

(I originally said expect, but in the session, I encouraged teachers to enjoy the errors that show a learner is progressing along the interlanguage spectrum.)

We went through several examples I called the “walk of shame” of language learning exercises asking for communication far beyond the learner’s current interlanguage. Click the slides to see more, but I’ll offer this one here. It’s asking for case endings on the Russian word for fish, to make it work in the sentence “I eat fish.”

Which of these options means “fish”? They all do. Am I ready at my spot in the Russian journey to know which case to choose for fish when I’m eating it as opposed to when it’s on the table? No. I am not. Especially when Duolingo is purporting to use natural input and doesn’t explain case, and the only reason I know what they’re asking for is that I’m a linguist, for heaven’s sake, and I know Russian has case and what case is.

I left participants with some guiding questions for developing effective i+1 lessons:

- What can you do that is purely passive?

- What tasks expect one-word output?

- What task expects two-word output where one word acts on the other?

- What multiword tasks come next?

- What’s the end goal (shooting for emergent fluency)?

And now, the resources.

Ready for some resources?

Here are the slides, including 2 lesson samples and application of this with tasks under Communication and Comparisons that you can ask for, with brief additional ideas for the other 3 C’s.

Here is the handout.

And now the end of every session… any questions? Comments?