Think about yourself and the bilingual people you know. How did you all become proficient in a new language?

A while ago, Marc’s post on 5 things to tell kids on the first day of class reminded me that I had done a survey related to that question. I felt like I discovered some important information, and I shared that information in my ImpACTFL voices talk at the ACTFL conference. I can’t believe I never shared it here. Let’s fix that.

Marc suggests we tell students this on the first day of class:

Acquiring another language is not hard, but it does take time. A lot of time.

and

Language class is different from every one of your other classes.

Now, I do take issue with people saying that language acquisition is “easy.” It is not easy. It is natural, but your brain is actually doing a whole lot of scientific work – making hypotheses, testing them, changing things. In first language acquisition, all this happens without the child realizing it, so it looks like it’s easy – they’re not aware of how hard the brain is working. (Nap time, anyone?) Arguably, any second language learner is much more aware of how hard the brain is working. But I digress.

You get the point. The way this happens is different from other learning processes, and it takes a lot of time. More time than we have in our classes. This brings up a very critical question about the goal of our classrooms. This question comes up a lot in conversations up and down our profession:

Isn’t acquisition the primary goal in our classrooms?

I argue that the answer is a resounding no.

Can of worms, opened.

Language acquisition is neither the only nor the highest goal of my language classroom.

Before you roast me over the coals, please hear me out. I have a lot of reasons for saying this, mostly having to do with advances in technology and motivation. I believe the primary goal of our language classes is this:

My highest goal is to inspire learners to involve themselves in language communities throughout their lives.

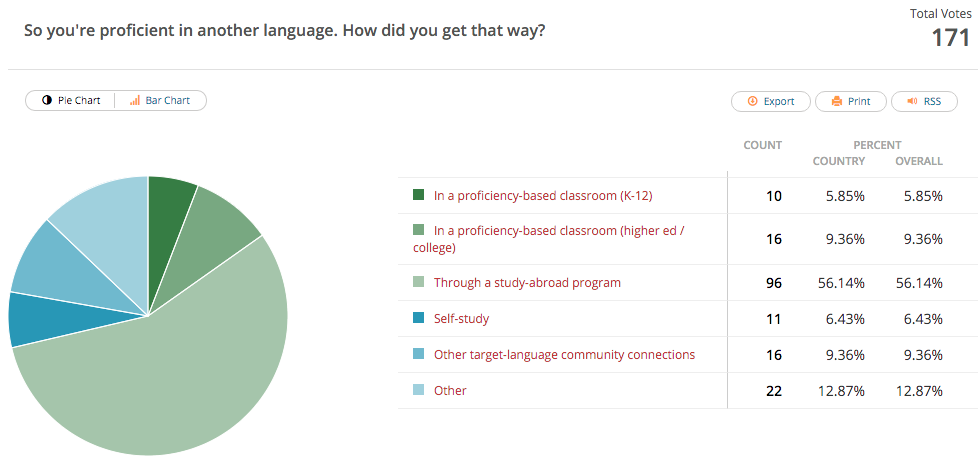

Why? Let’s take a look at the results of my survey. First, I asked this question:

So you’re proficient in another language. How did you get that way?

I offered these options:

- K-12 proficiency-focused classroom

- higher-ed proficiency-focused classroom

- self-study

- other TL community connection

- other

- study abroad

Digest these results for a moment.

Incredible. More than half the 171 people who responded – 56 % – said they became proficient through a study abroad program. This gave me serious pause, and it may you as well. Why? Because as I think back through the years of students I’ve accompanied on their Spanish journey, I know of fewer than 10 that went abroad to a Spanish-speaking country for any significant length of time after high school. There are probably a few more, but I know of just a handful. If you add that number to the people who say it was through other target-language community connections (this is me, my Advanced Mid Spanish proficiency is purely a product of in-USA TL interaction), the portion becomes more than 65%.

And the people who credit much of their proficiency in a proficiency-focused classroom? Total, K-16, 15%. That’s it. This number reflects something that’s been sneaking around in my mind for a long time: I’ve been in the language teaching field for -wow- almost 20 years, and I’ve met a lot of language learners, and almost none of them report developing their proficiency in a classroom.

How do we change that?

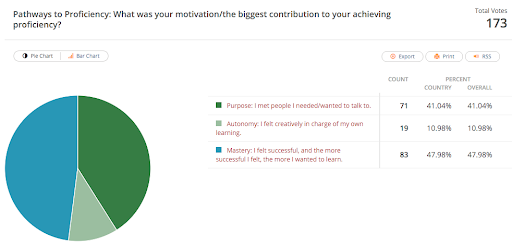

That brings me to my second and last survey question:

What was your motivation, the biggest contribution to your achieving proficiency?

The options were:

- Autonomy: I was creatively in charge of my own learning.

- Purpose: I wanted to talk to people.

- Mastery: I felt successful.

You probably recognize those options. They are the three aspects of motivation that Daniel Pink addresses in his brilliant book Drive. They’re very intertwined in what motivates us to do anything, but I wanted to know which was the predominant one in people’s pathway to proficiency. Mull over my results:

As much as we know student choice is a powerful motivator, very few chose this as their main motivating force. By a narrow margin, these successful language learners kept going on the path because they experienced success and slightly fewer because they knew there was someone out there to talk to.

Takeaway #1, and here’s where the acquisition-focused classroom comes in: if we create opportunities for success, learners are more likely to stay on the path to proficiency. Naturally, one of the best ways we do this is through acquisition focus. Teaching for acquisition helps students have fun and feel successful, both incredibly motivating experiences.

Secondly, learners are more likely to stay on the path to proficiency if we are continually, relentlessly laser-focused on this message:

There is a beautiful world of people out there who need to you to be their friend, to talk to them.

Culture-focused units do it. Community connections do it. Project-based learning with an authentic audience does it. This has been the mantra I found for my learners for the last few years, the mantra my father gifted to me that I forgot to weave into my own classroom in the early years: look at them, they could be friends. Go be a friend.

Let’s go teach for acquisition, for sure, but not for acquisition’s sake. Let’s do it as a way to keep kids on the path to speaking real language to real people. For life.

1 Comments

Comments are closed.

[…] were to the community. Especially after reading Sara-Elizabeth’s post, I would have them connect their project to the community somehow. I want them to get out and use their Spanish in some […]