I pledge allegiance to teaching with comprehensible input. Truly, I do.

Though I have perhaps a bit infamously blogged about where I depart from classic TPRS, including modifying translation as a way to establish meaning, where I land on the points of agreement/distinction in world language teaching, and how we need a couple of cures for our obsession with high-frequency words.

Still, I look forward every quarter to participating in an impromptu teacher PD group dubbed TCIKY that includes the likes of TPRS trainer Donna Tatum-Johns and CI novel author Emily Ibrahim. I think Martina Bex and Kara Jacobs are two of the best teacher-creators on the planet, bar none. I’m pretty sure I listened to every episode of Tea with BVP – I called in twice and I have all the swag – and I continue to catch Talkin’ L2 with BVP whenever I can (which doesn’t mean I agree with all of it). But there I go again.

The dissonance for me comes from the divided goals we must have in our classrooms. Yes, we aim for language acquisition, but we cannot ignore the changing employment landscape, the critical issue of motivation, the massive influence of individual differences, and oh, the time issue –

How can we pretend that we can replicate first language acquisition in our precious minutes per week?

But still, the way teaching with comprehensible input strategies engage students and set them up for acquisition success, it’s beautiful.

Conflicted with me yet?

Recently I was meeting with a school’s language department and in preparing to talk to them it finally dawned on me how to specify the “division” some of us feel when we start talking TCI. Sometimes it feels like we’re not actually talking about the same thing, and we end up in circles or in arguments. It hit me: it’s not about the targets or the input, it’s about the order.

Input –> Targets

One perspective to take when approaching teaching with comprehensible input is to start with the input as the foundation. So a teacher has found a news story, a crazy alien turtle story, a fantastic song, a cultural practice, an advertisement, a recipe, whatever, and that becomes the foundation of the lesson(s). This typically takes the form of mini-units, and there are a ton of them out there. It might be a unit based on a song or a commercial, but the unit is not organized around a theme in order to target a theme – the teacher takes the input and then determines what the target structures and language functions will be based on that input.

Here’s an example from my own instruction, for early middle grades.

Input: “Lola Aventuras: En el corazón de la selva”

Vocabulary / structures: place, jungle, there is/are, but, heart, amazing, pretty, all, they’re alike in some way

See the randomness of the targets? That’s because I came at the lesson(s) determined to use particular input and took the targets directly from it.

For me, this approach most often takes the form of a video guide. To see my Lola Aventuras guide and other tips for this approach, see my post on 5 steps to making a video viewing guide (with another big shout-out to Kara Jacobs).

Targets –> Input

The other approach is my primary method of teaching. It’s the way I first integrated TCI. It’s the way I blended TCI with ACTFL Can Do statements and proficiency guidelines. It’s also the approach I believe confused some practitioners who heard my verbal allegiance to strategies like TPRS but saw I didn’t take the usual order.

Perhaps this is my perspective because I came to this field first to textbook teaching; I never once heard of ACTFL or TPRS in my entire undergraduate training. Then I was introduced to ACTFL proficiency guidelines and Teaching with Comprehensible Input around the same time as each other. I was used to seeing a chapter with specific targets, whether grammatical (present tense regular verbs) or thematic (talking about food). And I wasn’t ready to say goodbye. So I explored my new storytelling strategies and Can Do tools by pairing them with these targets: “present tense regular verbs” became “I can say 3 activities people are doing at a party” with the input being, obviously, a party.

At the time, this approach blended well with my recently completed Second Language Acquisition courses. I took what I’d learned about such theories as the Noticing Hypothesis and targeted a particular conjugation (3rd person) while changing the color of the ending in the hopes that frequency + noticing would help mitigate how little time I had to pretend “natural” acquisition could happen.

So, though now I occasionally flip this approach to go from input to targets instead, this is still primarily the way I plan my units and lessons. Even when I have more or less random input selecting my targets, as I do this semester teaching the film Canela, before we encounter the targets in the film, I present input (usually a story) that patterns the targets for my learners.

Perhaps an example will help. Near the beginning of the movie, María’s grandmother tells her “I’m going to prepare a surprise for you,” to which María excitedly replies, “Is it going to be mole? Or cookies?” You can see what my targets are. So, it takes the better part of two 90-minute class periods to get through that one sequence in the film as we work with “Are you going to …?”, “I’m going to…”, and “(S)he’s going to…” in a story for input, at least one song, and several scaffolded conversation activities. This is how it takes us fourteen 90-minute class periods to watch perhaps 2/3 of the movie and then just sit back and relax and enjoy the end on the last day.

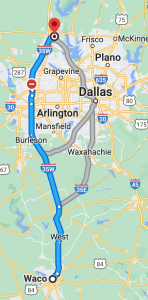

Between Denton and Waco, you can go through the DFW area two different ways: I-35E and I-35W. They don’t go from east to west. They’re two separate segments of the same interstate route. One runs to the east of the other, but both of them go from Denton down to the same conjuncture just north of Waco.

Between Denton and Waco, you can go through the DFW area two different ways: I-35E and I-35W. They don’t go from east to west. They’re two separate segments of the same interstate route. One runs to the east of the other, but both of them go from Denton down to the same conjuncture just north of Waco.

Not a perfect metaphor, but the next time it seems we’re going around in circles, pretty sure we’re talking about the same thing but somehow dangerously close to what feels like an argument, maybe we’ll discover we actually are talking about TCI together. It’s just you drive on I-35W, and I drive on I-35E, and I’ll see you at the destination – language proficiency.

3 Comments

Comments are closed.

I just wanted to tell you that while I totally understand why you are sharing your view points about CI practices, I also have seen non-CI teachers or more traditional teachers use your arguments as a reason to fuel their fire as to why they continue teaching the way they teach. All it takes is a google search of “against CI” or Why I don’t like CI and boom, they have all sorts of reasons to not want to use it. Just my two cents. (Personally, two different colleagues have cited your other “infamous” post as a reason why he/she doesn’t like CI. These people don’t even know what ci is and they continue using their traditional methods.)

Hi Katie, thanks for your feedback. It’s a shame that post is being used as any sort of justification for an opinion that someone “doesn’t like CI” – what does that even mean? Does it mean the person doesn’t agree that language is acquired through comprehensible input? Does it mean that there are specific aspects of a particular strategy that they don’t think is the most helpful way?

Wouldn’t it be so much more likely for us to end up at the same destination (proficiency) on slightly different pathways if we could talk that way instead: “I don’t use X strategy from Y approach because Z, but I can see why you do”? Surely a conscientious teacher knows how to evaluate strategies this way, but then again, there are many teachers not so interested in being that conscientious. Shame on them for making a baseless argument by twisting my words.

[…] writes another thoughtful piece about […]