It’s a myth, #11: Assessing communication without communication

For the original myths post, click here. You can also view all of the myths posts.

This, my eleventh post on myths I believe make us ineffective in the world language classroom, is about saying we’re assessing something without actually asking students to do it.

11. A multiple-choice question counts as a valid assessment of proficiency (or, “I can actually assess communication without asking students to communicate”).

Josué Goge

I don’t want to pretend that good assessment is easy. Exploring these questions-

- what is valid assessment?

- how can I make all my assessment valid?

- how can I do this without spending my life grading?

has been a long, difficult, worthwhile, amazing journey for me. From the days in my tests and measurements classes when I was required to write the very best Scantron test I could generate – whatever was easiest to grade – to now, when my philosophy is that students don’t answer a multiple choice question unless they’re doing AP prep, I have been on a mission to figure out what was wrong in the way I was treating assessment and fixing it. I’m not there yet, but I’m a lot farther than I was when I started, and as always, the journey itself is a lesson.

What’s wrong with non-communicative assessment

The answer to this comes down to two issues: goals and certainty.

If you’re going to use assessment that does not ask students to communicate, that may be fine, if communication is not your goal. That is, if you’re trying to motivate or ‘hook’ students using something like PollEverywhere at the beginning of class, or you want students to reflect on how they feel about what they learned in class in a type of reflective exit ticket, there can be a lot of value in that. The value evaporates when we try to say that we’re doing such an assessment to, say, assess whether students have learned to tell their name by choosing among

a) yo llamo

b) se llama

c) me llamo

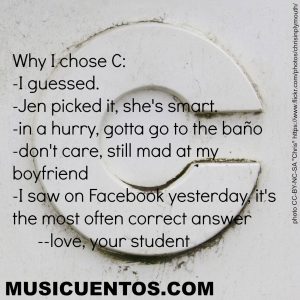

The other issue is with certainty, and this is my primary issue with the multiple choice question. When a student selects C in the above question, the answer is correct, but that does not tell you anything about why the student chose it. It cannot tell you this:

So you cannot be certain that the student actually knows the answer. You can only be certain that the student wrote C. And what does that tell you?

What communicative assessment looks like

Communicative assessment doesn’t have to be hard or extraordinarily time-consuming. It doesn’t have to look like a detailed IPA every other week. It simply has to ask students to communicate something. So, in the above example, instead of asking a multiple choice question, you’re asking students the question, “What’s your name?” If they can answer, you’ve assessed whether they can communicate that information… today, anyway.

interpretive

Interpretive tasks are the ones most prone to lack communication. And yes, I call it communication, because receiving a message is communication; it’s not a one-way street. There are so many muddy questions here. If I ask interpretive questions in English, is that appropriate assessment? I used to say no. I’ve changed my mind. Because on the other hand, if I ask the question in the TL, I’ve lost my certainty again. If the student gets the question wrong, is it that he misunderstood the message, or that he misunderstood the question/answers? I can’t tell. I watched this frustrate my AP students time and time again. They knew that the article was talking about people cooking a dish with pork, but because the comprehension question offered choices of extraordinarily low-frequency alternative words for goat, pig, and calf, they couldn’t select the right answer. So we assumed that the College Board cared more about whether they could comprehend these random alternative terms than actually comprehend the authentic text.

All that to say, my go-to way to incorporate interpretive tasks in a communicative program is to ask students to incorporate them into a production task. On the lower levels, I ask students to simply retell me what’s going on, or perhaps recreate with their own content (look at a ‘lost dog poster’ and change the information to their own pet, for example). For higher levels, they need to use the content to make a comparison or defend an opinion.

interpersonal

There’s an easy aspect and a hard aspect to interpersonal tasks. Easy: Ask students to have a conversation (in writing, maybe a Twitter exchange). If I’m assessing it, the conversation is with me. If it’s simply practice, the conversation can be with each other. Hard: don’t do skits and call it interpersonal. If students have a chance to draft and/or practice a conversation before performing it, this is not interpersonal. It can be valid, if you call it presentational, but it’s not interpersonal.

presentational

This is my primary method of acquiring test grades. I usually alternate or allow students to choose (but they must alternate choices): one presentational speaking or one presentational writing assessment per unit (that I grade). They may do lots of other presentational communication, even in every class period, as the definition is simply communication they have time to plan and edit. Their weekly blogs are a form of presentational writing. Bottom line, I’m asking them to communicate something in writing or speaking that we’ve been working on.

Novice example: Write a short review of your favorite restaurant for someone who is coming to visit our city.

Intermediate example: Compare the McDonald’s menu in Argentina with the McDonald’s menu here and tell what you like best and why. What would you eat at McDonald’s in Buenos Aires? Post your video presentation on YouTube (if allowed) and tweet it at McDonald’s Argentina.

More reading

Here are some previous Musicuentos posts that I think may help further with this issue:

- Putting a number grade on proficiency-based assessment

- Communicative grading made easier

- Abandon the multiple choice question

Consider this: what current practices are making our assessments invalid, and how can we change them (and maintain our sanity)?

5 Comments

Comments are closed.

Wow, I must have missed this post from earlier this year. Some really great food for thought. I was feeling pretty confident that I have been rewriting all of the assessments for my school to align with ACTFL standards but that follow along with our textbook series. Now I am going to re-think them. (of course, I have a couple more chapters to finish).

I have been creating end of the unit assessments which align with each chapter. However, each assessment had 10 listening questions, 10 reading questions, 10 interpersonal questions (more of an interview), a writing question and then some type of presentational speaking question (some times a role play). Your post here points out the obvious that reading and multiple choice questions are not communication. This is going to really reshape how I think things.

I am wondering if maybe I should assess reading and listening skills in a formative assessment and then the communication skills in a summative assessment.

This is such a timely post for me! I’ve been thinking about some of these things all year. My question: What do you let students *use* for their presentational assessments? Do they get a dictionary? Is there a maximum number of words they can look up? How can you police that AND do interpersonal assessments (assuming we’re at a unit-ending IPA that involves all modes of communication).

And for speaking – how much do they get to plan? Up to now, I’ve told my students that they can plan what they’re going to say, write it down, and practice it as many times as they want, but they can’t *read* it when they actually present. For more complex tasks I tell them that they can use notes or outlines, which must not be full sentences, and which must be turned in to me when they’re done.

Hey, Melanie – for summative presentational speaking, students know it’s coming and don’t usually work on it in class. They are allowed to use a 3×5 card with no sentences, only phrases and words, and I glance at it right before they start. I usually also do follow-up questions. It’s easy to tell if 1) it’s memorized and/or 2) they used a translator, the first being highly discouraged, the second being against the “law,” haha. As long as there are no sentences on the card, I don’t care what’s on it.

For interpersonal speaking, all they know is that it will relate to the theme we’ve been working on.

Hope this helps.

Here’s my take. It is a paradigm shift for so many of my teachers, and even me included, to really assess what students know and can do in the language. I like the idea of just forgetting about grammar and vocabulary and focusing on 1-2 skills that the students are being assessed on. A simple one-line rubric really helps this. That doesn’t mean you aren’t going to be ‘grading’–you need to consider the feedback that you are giving and when to give that feedback. If the goal is simply for kids to communicate, let them communicate and don’t focus on the little grammar and vocab. things–that will cause most to shut down and button their lips.

Thank you everyone for your valuable perspectives on this issue!