Why care about frequency?

If you want to remember why you care about high-frequency words, try learning a new language again. You’ll remember pretty quickly.

If you want to remember why you care about high-frequency words, try learning a new language again. You’ll remember pretty quickly.

In my recent journey to acquire some basic skills in Russian, I have more or less accidentally acquired three types of words:

- the ones I needed to say what I needed to say (such as, “У мне болит горло” – my throat hurts)

- Christian words and phrases because a lot of my interaction with Russian is via translated worship music and a local church service (I can come up with “Я так жажду Тебе” – I’m so thirsty for you – and “Я поклоняюсь Тебе” – I worship you – at the drop of a hat).

- the ones that are used the most.

In addition to giving me much greater communication power, knowing the high-frequency words gives me a shot of “YES I CAN” pretty often – or dare I say, frequently. Every time I hear the words for “want,” “only,” “know,” etc. I get a smile on my face, thinking hey, maybe I am getting some proficiency in this very new, not very easy Russian thing.

Hand it out or bulletin board it: Spanish high-frequency words

Earlier this year, I put up a new resource on TeachersPayTeachers that offered 195 of the most frequently used words in Spanish arranged by theme and type of word. I made that resource to be all on one page so that it would be an easy reference to hand out to students, or that it could transfer in its exact format to a bulletin board. But I knew I wanted to do something more with it.

When you hear about a word being “high frequency,” you probably know what that means. In analyzing lots and lots of language used by lots and lots of native speakers and writers (the term for the body of language used is a “corpus”), someone somewhere has shown that this word is one of the most frequently used words in the language. But how frequent? And what kind of sources were used? And how can I find, know, and use the words more quickly?

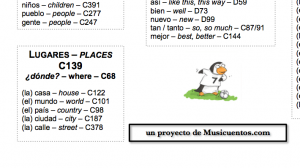

So, I took my chart and further expanded and divided it and categorized it. Then, I added the English translations. Then, I added the ranking according to the source I got it from. Now, it’s a three-page document with more than 200 high-frequency Spanish words with the English translation and a ranking number that tells you exactly how frequently it was used in the source’s corpus. Find it and purchase it here.

The pitfalls of using HF word lists

Be on the lookout for a post called “It’s not all about high frequency” coming soon. As I have worked on learning the high-frequency words and phrases in Russian, I find I still can do almost nothing with them. I can say I want, I need, I have, but I can’t say what it is that I need. I can say it’s four o’clock but I can’t say it’s eight o’clock. I can say it’s red but I can’t say it’s pink. I find I still desperately need the little pieces of language that fill out the meaning but because they aren’t used over and over don’t appear in the frequency lists.

The other problem is the types of words these lists are made from, and the types of sources. For example, in one of my sources, the CREA (Corpus de Referencia del Español Actual), they tell you where they got the language from:

…casi 140.000 documentos y algo más de 154 millones de formas procedentes de textos de todos los países hispánicos y producidos entre 1975 y 2004.

Los textos escritos, seleccionados tanto de libros como de periódicos y revistas, abarcan más de cien materias distintas. La lengua hablada está representada por transcripciones de documentos sonoros, obtenidos, en su mayor parte, de la radio y la televisión.

So because the words come from newspapers and magazines, radio and television, and because there’s no discrimination in what words are included, you can imagine what happened:

- gobierno is as high as 86, when we know “government” is not that frequently used in conversational speech,

- “Juan” is at 196 and “José” is higher than that because names aren’t filtered out,

- “embargo” is in there, ostensibly because it wasn’t included as a chunk with “sin,” when we all know that’s the only reason that word would appear in a list of HF words,

- Madrid is 140 (news sources!) and in fact, 353 is “M.”

Now, in the other source, the famed corpus analysis by Mark Davies, some of these issues are handled. His source is a

twenty million word corpus evenly divided between spoken, fiction and non-fiction texts from both Spain and Latin America.

One of the things Davies does is give you verbs in their infinitive forms, which in one way is helpful, because it shows you true frequency by grouping, say, 7 forms of a verb together to show you that it’s truly highly frequent. But in another way, it doesn’t tell you anything about which forms of that verb actually are most frequent.

My chart uses both sources, and in the chart, I tell you exactly which one I used, whether it’s the CREA or Davies, and if Davies, whether it’s from his overall list of the top 100 or one of his “top 25” lists like the 25 most frequently used verbs.

You may notice something else: some words we love to teach and use in Spanish class don’t appear anywhere in the lists, either in the top 500 from the CREA or even Davie’s top 25 verbs Think gustar and venir. Ones we like to use a lot for storytelling: ve doesn’t appear. In my more comprehensive document, I’ve eliminated some of these, but I’ve included others, so you can see exactly where our favorite vocabulary actually falls in this game of frequency.

Have a look and let me know what you think. Could a visual reference of high-frequency Spanish words help your students put more phrases and sentence together?