Meet Jack, the mean clown who wants to help you remember the map to TL Memory Lane.

Earlier this year, I blogged about the lessons we can learn from Lisa Genova‘s book Remember. Check out that blog post for a more in-depth look at the content of the book. I mentioned there that my dear colleague and friend Haylee Ziegler were going to present this topic at ACTFL ’23. Our session was called Teaching on TL Memory Lane, and it was a great time with great participants!

The purpose of this blog post is to serve as a sort of handout to our participants as well as those who couldn’t attend. (Yes! The promised slides are below!) We also want to share some suggestions that came up in our session.

Briefly, let me outline the content and add some highlights.

1. How you make a memory

Key takeaway: The number one thing you can do to improve your memory is pay attention. The problem is that attention is insufficient. It’s just a gateway to your working memory, where you keep spoken words about 15-30 seconds before getting rid of them. In order to make a memory, your brain has to believe that something about this moment is worth keeping.

Essentially, your brain follows two steps to make a memory. First, you perceive something with your senses. Then, your brain changes. How? Through the four steps to making a memory:

- encoding (translating input to neurological information)

- consolidation (linking pieces of input, like how the car sounded, plus the color of it, plus the person driving, plus the words she shouted, like weaving a tapestry)

- storage (formatting the information to be “persistently maintained”)

- retrieval (activating connections to remember them, which cements the memory further)

2. Types of memory

There are three types of memory:

- Semantic memory is data unattached to a specific life event.

- Episodic memory is personal and always about the past.

Improve it by asking learners to look up from devices, shake up the routine, and write something down.

Hot take: The deskless classroom is not necessarily supporting learner memory. Consider a rule from my classroom: Keep your composition notebook close, and if I write it, you have to write it. - Motor memory is how you know how to do things, like ride a bike.

It’s remarkably stable and doesn’t degrade with age.

Hot take: Requiring output and addressing pronunciation problems is a solid memory strategy. Unless the learner brain trains the muscles in the mouth and face to form the words, off-target pronunciation can impede comprehensibility.

3. The Map to Memory Lane

Genova’s book identifies five features of very strong memories that we suggest you incorporate in your input strategies and general class environment:

- Repetition

Hot take: It is possible to tell if a learner is putting in effort.

Hot take: Language learning is not actually easy. The brain is working hard during the whole process.

Incorporate repetition in your class by a) recycling themes, structures, and vocabulary across units; b) asking for retrieval after learners have slept (sleep is essential for the brain to encode memory) and c) use strategies like retrieval grids (see the book Make It Stick) and flashcards.

Hot take: Flashcards have value. Old school isn’t always bad!

Hot take: Language class doesn’t provide enough time for enough repetition for broad acquisition. Be content with deeper memory of few words and structures, inspire learners to keep going, and be encouraged that if they leave language learning aside and pick it up again later, the trace memories left in the brain will make it easier the next time around. - Meaning

Wrap meaning around everything in order to foster better memory. You’ll struggle to remember there’s a Rutgers basketball player named Baker (I mean, unless you just really love Rutgers) but if I introduce you to a baker named Baker, suddenly you’ve connected the name to an outfit, smells, a taste – and a year from now you’ll be like, “Oh yeah! That’s the baker who was actually NAMED Baker!” Meaningful connections.

Use stories, sounds (like the “dr” sound in taladro helps my construction supervisor student recall that it means “drill”), and caring- help students care about the content. Suggestions for helping them care include tailoring content, offering student choice (check out my post on homework choice options), and ask for opinions regularly- learners can get passionate about their opinions on many topics!

Hot take: Memorizing translations of target language words does not create deep neural connections favorable for memory retrieval.

- Emotion

You remember where you were when 9/11 happened or when schools shut down for COVID because emotion sears memory into your brain. These are called “flashbulb” memories. Evoke emotion using class polling, supporting input with highly engaging and dramatic video clips, incorporating Socratic seminar discussions, and playing more games (fun!). - Novelty

- Surprise

They’re not the same- what’s novel is not always surprising- but they’re close enough that we put them together.

Hot take: Connecting input to craziness is a solid memory strategy. So keep telling those crazy stories!

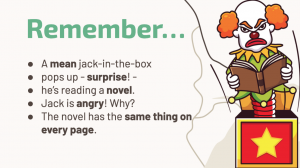

We created a mnemonic character, Jack the mean clown, to help you remember these five elements:

There you have it- meaning, surprise, novelty, emotion, repetition.

We asked participants to take a look at three meaningful but forgettable tasks typical in a world language classroom, and suggest ways they could add these elements to the task. Tasks included comparing your school schedule to that of a classmate, creating a Pizza Hut menu in the target language, or describing an animal at risk in the rainforest. We didn’t have a lot of time for discussion and sharing, but a great suggestion was to make the menu like a Fear Factor menu, including such delicacies as crickets on the pizza.

We ended with three takeaways of things you could do next week to put this information into practice (besides reading Genova’s book!):

- Write: Have learners write information down during an activity.

- Retrieve: Make an exit ticket or other retrieval practice about information several days or weeks old, not what was learned that day.

- Refute: Spark a debate, create a mnemonic character, or otherwise connect content with emotion and surprise.

On the topic of that last suggestion, by mnemonic character I mean an image that helps learners remember vocabulary and/or structures. I have long been on a slow journey to develop proficiency in Russian, and I recently started creating my own mnemonic image each week to help me learn 4-5 new words. This week, my mnemonic image is a cow named Rover with a noose around his neck. He’s standing on the road to Brementown, and he’s holding an empty bowl- the bowl had time in it, but it’s empty now, because he needs more time (I mean, there’s a noose around his neck). My memory sentence is “Корова говорит: «Мне нужно больше времени».” It sounds like this: Korova govorit: «Mne nuzhno bol’she vremeni». Get it? Cow-rover (govorit – a word I already know) noose – bowl – Bremen. It means, “The cow says, ‘I need more time.’”

And of course, the promised slides.