Better acquisition by altering (not eliminating) translation

I think I’ve come to the end of the acquisition vs. learning distinction for the purposes of language learning in a classroom.

Rewind. When I first started investigating second language acquisition research, I was blown away by what I learned about how people really learn languages. It revolutionized my classroom. It brought me to incorporate comprehensible input instead of explanations of how language works. It led me to guide students through experiencing the language instead of dissecting it.

But then the more I read about how language for communication is always acquired and never “learned,” and how “learning” is conscious and “acquisition” is unconscious, a burning, itching, annoying question kept popping up in my head: but how can we know it’s unconscious? In particular, how can we know it’s unconscious when the sign over my door says SPANISH CLASS? I just can’t reconcile it. I can’t see how it makes sense to say I can tell whether it’s learning or acquisition. To go farther, I can’t see how it makes sense to say that it’s unconscious acquisition at all. (One exception that does make sense to me is in immersion classes, where, for example, a fourth-grader is learning science in Spanish and not knowingly learning the language.)

But it is acquisition, say you, because you can tell. Because the input is so compelling and compelling input causes acquisition. You know it’s acquisition because the input is compelling. And how do you know it’s compelling? Well I know it’s compelling, because they said “yay!” or they perked up or they said “I love Spanish class!.” (Hmm.) And because they’re acquiring the language. It’s obvious in the output, right? They’ve acquired it. And acquisition means the input was compelling. And compelling input means it’s acquisition.

It’s a totally circular argument, is it not?*

But what if it was learned? And is still useful for communication? If I can use the language, who cares whether it was learned or acquired?

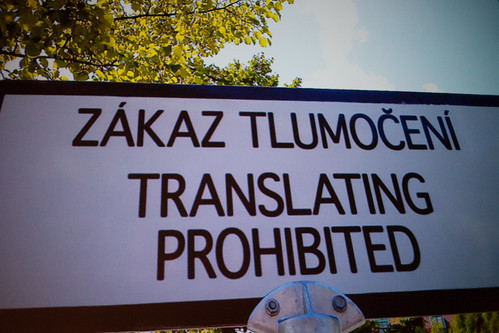

Anyway, I digress. You came here to talk about translation. I started with acquisition vs. learning because I first want to establish that I’m normally using the two terms interchangeably, even in the title of this post. I do not believe I can be completely sure what I’m looking at is either acquisition or learning. I do know some things, though, that help me think more clearly about the issue of translation:

Anyway, I digress. You came here to talk about translation. I started with acquisition vs. learning because I first want to establish that I’m normally using the two terms interchangeably, even in the title of this post. I do not believe I can be completely sure what I’m looking at is either acquisition or learning. I do know some things, though, that help me think more clearly about the issue of translation:

- Kids develop language skills faster when they comprehend what’s going on.

- Kids develop language skills faster and better when they interact with more target language over any given period of time.

- Memory gets stronger when learners encounter “desirable difficulties.”

- My learners do not have enough time for natural acquisition to happen in my classroom.

- I have lots of tools at my disposal to help me establish meaning and know that students have understood.

- YOUR LEARNERS DO NOT HAVE ENOUGH TIME FOR NATURAL ACQUISITION TO HAPPEN IN YOUR CLASSROOM. Even if we could present it that way, which is highly doubtful.

Now, as for translation, I know there are two positions:

- Translation is not useful for language acquisition because it connects the new word to the native-language word instead of connecting the new word to the concept in the brain. (I agree.)

- Translation is the fastest way to establish clear meaning for new structures, and establishing meaning is vital for acquisition. (I agree.)

When, as in this case, I agree with both poles of the field, I know that the answer for me is going to end up to be somewhere in the middle. So here I present a couple of ways I both eliminate translation and alter it without eliminating it.

1. Image. Check. Translate.

Image: My friend Carol tells about when she tried to establish the meaning of agua by holding up a water bottle, and sometime later found out that one or more of her students had understood the word as bottle. To me, this isn’t a reason for offering translation; it’s a reason to give more visual examples. If I talk about agua and I show a Dasani bottle, water coming from a tap, rain drops, a waterfall, and a puddle, students are far more likely to comprehend the meaning in a way that more effectively cements long-term memory. Bonus: This approach gives me many more repetitions of the target word/structure.

Check: After a few examples, I ask for a thumbs-up or X sign to check if students believe they comprehend the word or phrase.

Translate: If a few students are still unsure, I will ask someone to guess what it is. I don’t translate it myself unless I have to. Someone says “water?” and I nod, high five, thumbs-up, or some other affirmation and move on. If everyone’s sure they know what’s going on, and the concept wasn’t one I think they would have mixed up, I don’t translate it at all.

2. Example. Example. Example. Example. Check. Translate.

Example: The word is “magazine.” What’s a magazine, guys? Let’s see, an example of a magazine (“example” is a very early target for us because we use it so much), Seventeen is a magazine. GQ is a magazine. Rolling Stone is a magazine. Entertainment Weekly is a magazine.

Example: Hey, Amelia, what’s another example of a magazine? Great, yes, Lucky is a magazine.

Check: Who understands “magazine”? Thumbs up/X?

Translate: Hey, Jack, a couple of people are confused; tell us in English, what’s “magazine”?

And what if they do mix it up?

So what if that one kid did think that agua meant faucet and we don’t find out until two weeks later? So what? It happens all the time in language learning. In my own journey, I find it a desirable difficulty: remembering that I had it a little wonky, and what the real concept was, and what the word is for the thing I thought it was, helps me remember it better and longer, and I got two words for the price of one.

Is translation ever the first course of action?

For me, yes. If we’ve encountered something in a resource that’s not a target structure and students really want to know what it means, I quickly translate it. Especially if it will make them laugh. If it’s a complicated concept like to take advantage of and I know I’ll waste 10 minutes trying to get it across in the target language and half the class still won’t get it, I translate it. All my vocabulary lists until intermediate are translation-based, though they never see the light of day in class; they are only a pre-class resource.

When in doubt? There you have my go-to strategies for altering translation without eliminating it: lots of visual and verbal examples, and students doing the translating for me.

*I’m not trying to be trite or dismissive; I’m asking a real question and dying for someone to take up this conversation with me, and no one seems to be willing. The last time I asked it, no less than Bill Van Patten totally dismissed the question with, “Of course acquisition happens in a classroom.” Because he said so. So if you’re willing to engage in this conversation with me instead of dismissing it, to help me figure out the real problems here like how we can apply first language acquisition principles to a situation that looks almost nothing like first language learning, and how students can develop lasting proficiency when we don’t have the time they spent doing this the first time around, please! I want to explore this.

13 Comments

Comments are closed.

[…] via Musicuentos – Better acquisition by altering (not eliminating) translation. […]

Thank you! Thank you! Thank you! I was taught and student-taught in classrooms that leaned more towards traditional methods even though they incorporated elements of pure proficiency. As I move my own classroom towards something that offers more proficiency-based components than traditionally explicit instruction, I appreciate that this post acknowledges the middle ground.

Thanks for this thoughtful, characteristically balanced post, Sara-Elizabeth! You might be interested in these alternatives to translation that are used in language immersion camps where I sometimes teach. Both teachers and students are taught these alternatives in L1 before entering full immersion. Different tactics may be more suitable to expressing different concepts:

Express the meaning…

1. by showing a physical item

2. through gestures

3. through a picture

4. by giving (near) synonyms

5. by giving (near) antonyms

6. by listing examples / members of a category (e.g., if the target word is “country,” listing several countries whose names are transparent)

7. by defining the word in the TL

8. by means of a scene/skit

Teachers and students also undergo training in how to “triangulate” to a target word/meaning to minimize ambiguity in as few steps as possible.

Like you, I don’t see a need for eliminating translation when there is a shared L1; in fact, I use it quite a bit more than I used to, partly because of the time problem that you emphasize. But in settings where people (teachers or learners) either (a) are opposed to translations or (b) have agreed to create/simulate full immersion, the techniques I’ve listed are really handy!

Thanks so much for those additional tips, Justin!

Thank you, Sara-Elizabeth! I believe in CI, but sometimes it takes so much time to get students to understand a certain word or expression, and our time with students is so limited. Your guideline here is perfect, along with the additional comments by Justin!

Thanks for the comment, Myra – really, I think I live with a lot more peace when I remind myself the answer is almost always somewhere between the two poles!

I have always felt conflicted when the opposition of “learned” vs “acquired” was brought up because in my language journey/experience they feel so interconnected. As someone who’s been primarily operating in L2 for the last 17 years (with a healthy dose of L3 and L1 daily), I am still encountering “learn = > acquire” scenarios. Here’s the most likely one. I read/hear something and I don’t know the word or nuance or register… so I turn to the nearest native speaker and ask. With no native speakers, I reach for the dictionary. Sometimes native speaker (my husband) and I argue, so two dictionaries come out as we both want to prove our point. I might need to encounter this word again and again, and repeat the whole thing. But eventually, it makes it into my passive and then into active vocabulary. The line between learning and acquisition here is so blurry that I see no point in arguing how it happened. Does it even matter if I defined the word in English or translated it into Russian?

And why LEARNING has become a negative word? My best students will make an effort to try the new expression/structure as many times as they can during the lesson. Their efforts pay off in better variety of vocabulary, more interesting sentence structure and thus higher proficiency. Speaking of proficiency… Does it matter if a language teacher learns what proficiency means or acquires the term as long as he aligns his practices with it?

I could not agree more, Natalia. I’ll be reposting Justin Slocum Bailey’s response to my request for conversation and it really helped me understand that when many people are throwing out the word “acquisition” they aren’t saying it’s totally “unconscious.” And I’m on the side of the linguist DeKeyser, here, I think. I know I am using grammatical explanations – very conscious learning – to adjust how I talk and communicate better. I do it all the time. I know it slows down my communication and makes my speed less native-like. I don’t particularly care. It helps me communicate more accurately, which is what I want to do.

Thomas asks the same question – why is learning a negative word, particularly in language teaching? I used to be a big fan of the distinction and go on about how students can’t learn language for communicative purposes, it has to be acquired. As usual, I’m coming to a position much muddier in the middle, and honestly, I really like the nice comfy mud.

Great points, Natalia. Your example confirms what many observers and theorists describe: once a person has a really solid Mental Representation of the language, new items may be incorporated into to it with only a very few encounters with the item, and sometimes even just by the person’s being told what something means or how it is used.

I similarly lamented the unintended negative effects of the acquisition-learning distinction in “The Bummer about ‘Acquisition,’ Part 1: ” http://indwellinglanguage.com/the-bummer-about-acquisition-part-1/

The comments on that post are really helpful. Short summary of the post itself: It’s worth distinguishing between the processes meant by “acquisition” and “learning,” but the fact that “learning” came to describe a secondary goal of language courses can lead to misunderstanding and even open the door to intentional criticisms that can distract from the main issues.

<3: "intentional criticisms that can distract from the main issues"

[…] on the learning vs. acquisition dichotomy, particularly in the context of translation, in the post Better acquisition by altering (not eliminating) translation.” (Finally! Someone is willing to talk about this!) Justin and Indwelling Language […]

[…] My post on acquisition in the language classroom […]

[…] I have perhaps a bit infamously blogged about where I depart from classic TPRS, including modifying translation as a way to establish meaning, where I land on the points of agreement/distinction in world […]