Best of 2014 #4 & #8: Curriculum planning outside the textbook

It’s time for the 8th most popular post of 2014, which was the second in a two-part series, and it just so happens that the 4th most popular post of the year was the first part in the series. Since it makes sense to read them in order, I’m offering them both to you here. They detail the process I go through to develop curriculum plans with or without a textbook. The first post is about what I do in the summer(ish), and the second is about what I do as I’m going to begin each unit.

If you’d like to work with me on putting this process to work in a way that works for you, then you’ll want to come to Camp Musicuentos. We’re doing two locations next year: Louisville, Kentucky and Warwick, Rhode Island.

Part One

I’ve been told several times recently that the concept of planning your own curriculum is all well and good, but where do you start? What steps do you take? Now that I’ve been textbook-free for five years, I’ve refined my own process to the following steps.

Before school starts

If you think you have to have everything planned before the first day of school, you really have a daunting project ahead of you. Here are the steps I actually take when I write and rewrite curriculum maps and guides (which I have done every summer for at least one subject – always tinkering!).

-

Become familiar with I Can statements and proficiency standards.

Visit and revisit the ACTFL or good state standards and I Can statements for the level you’re planning. Ask yourself, what can a student at this level do? Where are we headed? What will our goals be? As an example, if you’re looking at a novice curriculum, keep in mind the overarching principle that novices can talk in simple ways about topics that are familiar. -

Sketch a list of topics and potential units.

The key here is your overarching, guiding question. If novices can talk in simple ways about familiar topics, what are the topics that are familiar to them? Well, the ones that are part of their world: family, school, friends, fun, routines, places, and so on. - Actually delineate what the units will be.

Narrow units to a number that fits your calendar; between six and nine is a good number and fit well in a 36-week school year. Resist doing too many and remember that most language teachers address too much content. As you look at your list of topics and develop a title and focus for your units, think about activity, not language function: “Around town with my friends” helps you focus on communicating meaning, and may include vocabulary and grammar related to shopping, numbers, describing, transportation, making plans, and eating out. -

Schedule your units.

Look at your school calendar and set dates to start and finish the units. I begin a spreadsheet and run the dates along the left column, including the day of the week, date, and which week/day it is (so Tuesday of week 3 is 3-2, unless the Monday was a holiday, in which case it’s 3-1). -

Assign I-Can (or Can-D0) statements to your units, working from last to first (for more on backward design, see Understanding by Design). What will students be able to do at the end of this unit?

-

Plan and date assessments.

This is why it’s critical to choose level-appropriate Can-Do statements before you plan assessments. Ask what your students can do as one or more integrated performance assessments to show you that they actually can accomplish what you set out to achieve. Then date them near the end of your unit. I have small classes and long units, so I currently plan my performance assessments by mode with 4 per unit: one interpersonal speaking, one interpersonal writing, one presentational speaking, on presentational writing (and the presentational assessments include interpretive because students are required to incorporate authentic sources). However, if I were planning now, in light of the evolution of the IPA and for large classes, I would plan two and have them be more integrated. In shorter units, I would plan one.

That’s it – that’s the bare bones of what you really ought to have planned out before school starts. Not so much to do this summer, right? Stay tuned for the next installment to find out what I do before each unit begins.

Part Two

To find out what curriculum planning I think is necessary before school begins, click here for Part 1.

Before the unit starts

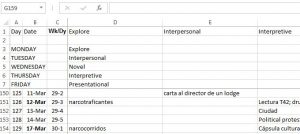

- If you haven’t already (see Part 1 #4), choose a platform to help you organize yourself. I use a simple Excel or Google Drive spreadsheet.

On the left, I list the date, number of the week and day in the school year (so the second day of week 12 is 12-2), and the actual number of the day in the year (day 84, for example, so I know how many days we’ve met). But I like data. Use whatever works for you.

Along the top, I use the categories I use for planning: Explore, Interpretive, Interpersonal, Presentational, Assessment, and Resources. That way, I can look at it and quickly determine if my activities are too heavily weighted in one area.

-

Since you know what your units will be and have a good idea of what your assessments will be, look at the first unit’s assessments. Ask yourself: What do they need to do the assessment?

Examples:

If your assessment goal is “I can say what I want in a hotel” then students will need tools to express wants/needs/preferences, and vocabulary about hotels.

If the goal is “I can talk about why I like a place for vacation” then students will need vacation vocabulary (transportation? geography? activities?) and will need tools to express likes.

Let’s say a goal is “I can tell my friend some activities I’m going to do on vacation.” Then students need activities vocabulary like “going to,” “have to,” and perhaps days of week and telling time.

The key is that you’re looking at everything in terms of meaning all the time. It’s not that you’re never approaching grammar. You have to. If students are going to talk about what they’re going to do, they’re going to need to be able to use the “going to” construction. But the point is to talk about what they’re going to do, not to use the “going to” construction. -

Consider the vocabulary they need. I still advocate developing a short list of potential vocabulary they’ll need. You can’t control what they’ll actually acquire but let’s face it, especially at lower levels, some of the vocabulary to do particular things will be common. To talk about what they’re going to do, all students will end up using words like eat and sleep.

-

Look at your end goals again and ask: what grammar will they need? Develop a short list of structures you’ll need to hit, like “quiero,” “me gusta,” more opinion phrases, descriptions, and “ir + a.”

-

Brainstorm the activities; come from the assessment and go from end to start. What should they be doing immediately before the assessment(s)? What other things can they do to get there? Go backwards from there.

In our example, if they will need to talk about vacation places, what activities can we do to practice to get them there? Some may be from a textbook. Perhaps they’ll look at place reviews, or official amusement park websites or a tour guide article. Maybe they’ll watch a YouTube tourism video and put comments in order or categorize them as true or false. Maybe they’ll watch Disney commercials and do cloze listening quizzes and answer questions about trips to Disney. We’re brainstorming communicative activities all designed to get us to the goal: our proficiency-based performance assessment.

To help you come up with ideas, ask yourself, what authentic resources can students explore? Then, ask: “How can I preview them and make them more comprehensible? How can they help us develop more vocabulary? What will we do with them? What will we do after them? How can I verify students are exploring and comprehending? Will I give a comprehension quiz on Edmodo? Ask for a summary? What deeper thinking can I inspire from this resource? How can we build a conversation about the activity? Here’s an example of this process:-

brainstorm vocabulary related to going to an amusement park

-

students do conversations about trips to amusement park (add to vocabulary)

-

make a class list of what makes a great amusement park

-

order some activities you might do at an amusement park (time of day, before/after/during/while)

-

look at authentic amusement park resource – give your opinion and why you think that

-

with a friend, plan activities at this amusement park and report on your plan

-

do the same thing with another amusement park, different in theme

-

compare the two parks

-

make an infographic about the one you like better

-

report which one you like better and why

-

graphically represent how many students in the class liked one or the other and reasons why

-

-

When you have more activities then you could ever need in a unit (always plan too much instead of too little!), plot the sequence of these activities in a logical way so they build on each other. I fill in the cells on my spreadsheet with these activities. I can easily move them around to reorder things according to what I think will work best and help students learn better.

-

As a storytelling teacher, the last thing I do is consider an outline for a story to introduce the theme. This is the method I choose to present structures and vocabulary using comprehensible input. Students need to assimilate at least some of the language before I ask them to do anything with it, and I honestly don’t know how other teachers communicate this content in a comprehensible way without storytelling. Consider whether you need to do more than one story in your unit. And, will students do anything with the story once it’s done, or will we just launch into activities?

The above is what I do before the unit begins. This process takes me between two to four hours, depending on the length of the unit and how hard it is for me to find the resources I need. Note that what I’ve done is to map out the whole unit – I know what we will do each day. That doesn’t mean I have each day planned out. So I still have one thing left to do.

-

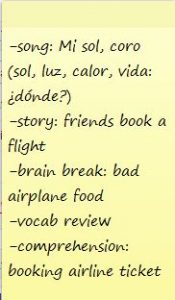

The Friday, Saturday, and/or Sunday before each week of my unit begins, I look at the week and plot what exactly we’re doing. If I need to make sentence strips for a true/false activity, I do it now. If I need to make a cloze quiz, this is when that happens.

For teachers in the first couple of years of your career, I have one more recommendation. Every morning, look again at your plan. On a sticky note, write the exact sequence of what you’ll do. This way you’ll know for sure you have everything you need and you won’t have to think, “Wait, what was I going to do next?” Put this sticky note on your laptop, textbook, notebook, whatever you keep with you a lot in the classroom so you can refer to it. This tip kept my classes moving smoothly in those difficult first couple of years.

If you want to see more examples of curriculum I’ve worked on, here are some materials we began developing for our Spanish 1 curriculum a few years ago. We weren’t able to finish them but they’ll give you an idea of where we were headed.

To add one more thing, also relevant is the question of how this all plays out in a gradebook. At my school we are required to count “daily grades” as 50% and “tests” as 50%. Here’s what that looks like for me:

- Daily grades:

-weekly homework choice activity

-blog on Edmodo

-listening cloze quizzes such as for commercials

-comprehension quizzes on authentic resources

-presentational or interpersonal practice, such as an infographic students create and email to me or a letter they write to someone

-chapter guides on our novels - Test grades:

-one or more integrated performance assessments (I used to plan one interpersonal speaking, one interpersonal writing, one presentational speaking, and one presentational writing, but now I would plan one or two assessments involving more than one mode in the same assessment)

-another test grade is the cumulative points correct on all quizzes, including our novel reading guides

For further clarification, I never ask multiple-choice questions, and my quizzes are always unannounced.

I hope this helps you on the journey to making your curriculum your own, one that works for your students and you in your classroom, a situation that doesn’t exist anywhere else. It may seem tedious, but I think the process I’ve laid out here will make it a lot easier, and after you try it, you won’t want to do anything else!

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

[…] year (my 5th) is my first year using long term unit plans (with more than a little help from these tutorials by Sara-Elizabeth Cottrell!) and it has made things much easier. Instead of teaching.. uh, stuff, […]

[…] my own research and professional development, will you let me sequence tasks and offer practice in a way I believe will offer my students better opportunity for growth if I can […]