A friend of mine told me he frequently gets asked if I’m a TPRS teacher. My answer: TPRS is an am vs. use question for me. Yes, I use. No, I am not “a TPRS teacher.”

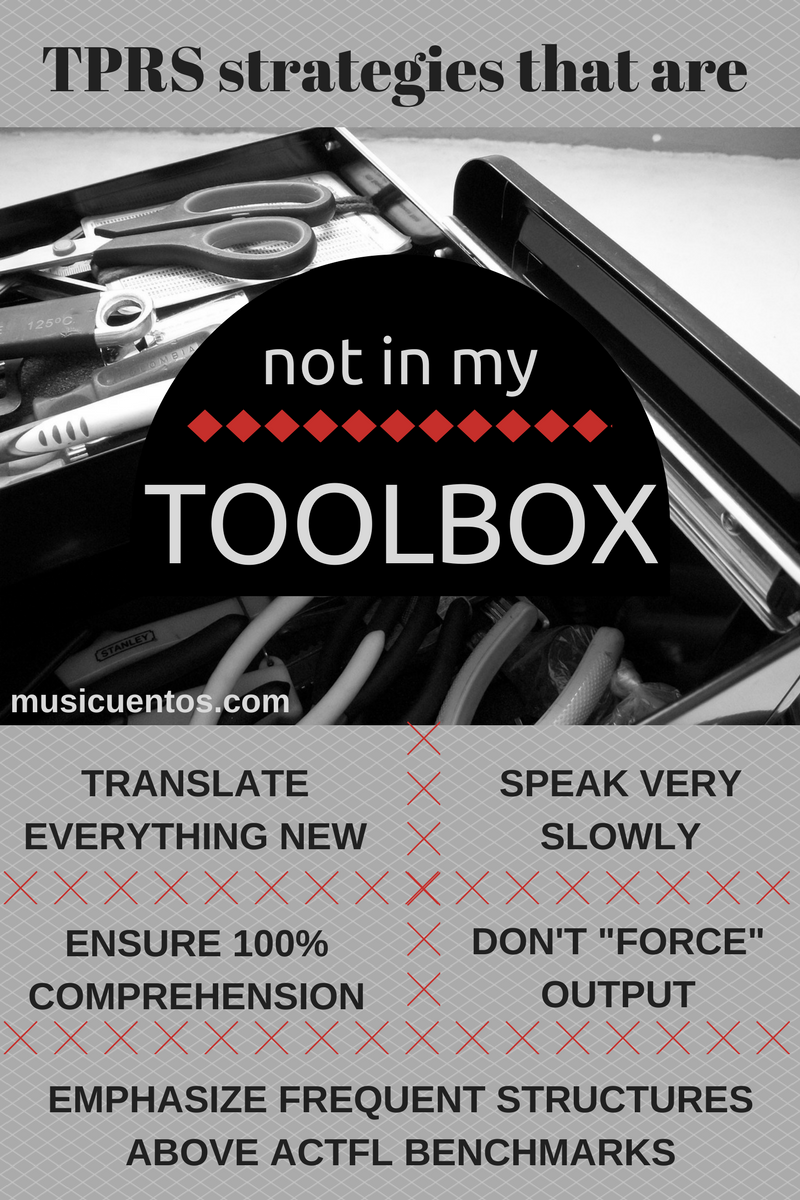

There are so many strategies from TPRS that have made me a much better teacher and that I use in almost every class period. I wrote about them in “What I Love about TPRS.” On the other hand, there are several strategies and principles in TPRS that I simply leave aside, for various reasons. In no particular order, here are some things that, as my preschooler would say, “crack me nuts” about the teaching method known as TPRS.

It’s about time.

Believe it or not, the field of Second Language Acquisition research has long been divided on the question of whether people acquire their second language by the same process by which they acquire their first. As I wrote in my “what I love” post, Stephen Krashen lands in the “yes” camp. He thinks that the process the second time around is much the same. Bill Van Patten agrees that they are “fundamentally similar.” Therefore, if you can reproduce the L1 (first language) process you’ll be successful in L2 acquisition.

My opinion: I think the process would be the same if we could reproduce the ingredients that led to acquiring the first language. The problem is, we can’t. There’s no maybe here. We absolutely can never reproduce the L1 acquisition environment.

All of my departures from TPRS stem from my disagreement here. It thinks it can reproduce L1 learning and it just can’t. And then it figures out it can’t and tries to make up for it in ways that don’t make sense to me:

- Fact: Learners know what language is supposed to look like. They know how to think about language. This is called metacognitive awareness. Babies are just getting it. Children already have it. This has to cause a difference.

TPRS solutions:

1) English translation of every target structure. They’re going to do it anyway, why not do it for them and make sure they get it right?

2) Pop-up grammar. They’re going to think about the grammar, why not explain it in brief spurts and then move on? - Fact: There’s not enough time for randomness. My daughter still says taughten and she’s heard English every day since she was born. She still says yo tieno and she’s heard Spanish from her primary caregiver every day since she was born.

Children do not attain an adult grammar of their first language until they are about 8 years old. EIGHT YEARS it takes. Even if we could reproduce the L1 process, we simply don’t have the time.

TPRS solution: “Shelter vocabulary” by targeting the structures and vocabulary shown to be used most frequently in the target language. - Fact: Comprehensible, engaging input is very, very important for successful language acquisition.

TPRS response: Make sure students understand everything they hear by translating everything and going really, really slow.

My choice: Leverage metacognitive awareness.

Learning language the second time around has one huge difference that has to impact how students approach the learning: metacognitive awareness. That is, they know how to think about their language. They can think, wait, I did that wrong, what was that again? why was that word there?

Students know what a subject is (even if they can’t label it-I don’t mean grammatical labels here). They know what a verb is. They know what order words are in in English. You can’t pretend they don’t. Well, you can, but they’re going to transfer this awareness anyway, so you really ought to find a way to take advantage of it. Why? You guessed it, there’s not enough time to discount it.

My choice: Pattern input for inductive learning.

When people acquire their first language, there’s not a lot of pattern to it – that is, no one sits and decides to teach their 2-year-old present tense regular verbs. How to pluralize words. Objective and nominative case. So, if it happens the same way the second time, why not just do it randomly? Ben Slavic, one of the biggest names in TPRS training, advocates this random approach. I am on a completely different road from Ben here.

Ben:

I do not spend a lot of time attempting to “integrate” certain words into some kind of pre-arranged list of vocabulary from week to week, but you can if you want. I find that doing so stilts the quality of the stories.

Me: I make fun stories that contain patterned target features I want my students to master (e.g. using quiero and demonstrative adjectives to express which thing they want from a selection of things). I want them to extract the pattern so they can apply it to other words.

Ben:

It is easy to see why some of the best TPRS teachers just prefer doing PQA [the practice of asking students highly repetitive questions about themselves] the entire class period, just talking to the kids instead of doing stories.

Me: I cannot convince myself that NOT having a goal other than my communicating language to students is the most effective way to improve my students’ proficiency. And click the link above and see the example that inspired this comment. It’s not easy to see. This would drive my students crazy in pretty short order. (The TPRS response to I’ve heard is that you’re just not doing it right; if you were doing it right, your students would always be quite engaged.)

Ben:

Notice that I try to keep the PQA hooked to the original phrases, but that is certainly not at all necessary in PQA. If the discussion strays from the structures, it doesn’t matter. You are interacting with the kids in the target language, which is the entire point.

Me: Hmm. Maybe it’s his entire point. It’s not mine. That is perhaps my most important point in the novice classroom, but I have a lot more points than that.

I could go on. But I won’t. Summary: I choose patterning over randomness because this isn’t first language acquisition. And there isn’t enough time.

My choice: Avoid translation of every target in the interest of desirable difficulty.

TPRS’s major departure from the first language acquisition process is that relies heavily on English translation. You’re supposed to translate your target features for your students into English, always, immediately. But this doesn’t mesh with the way research has theorized vocabulary is arranged in our brains.

If researchers are right and vocabulary is more entrenched in the right kind of memory when it’s tied to the concept instead of the English word-

If researchers are right and a certain amount of difficulty actually creates stronger, longer memories-

Then, why are we using so much translation in the classroom? I really end up closer to OWL in this area.

Ben:

I want to buy a butterfly, class!

Butterfly is a new word, so I write butterfly down and give the English. This sentence may lead to a discussion lasting one minute or the entire class period.

I can understand translating something like take advantage of into English because it takes too much time to get it across another way, but in my opinion, it just doesn’t take that much time to draw a butterfly.

But what if students think you mean “monarch,” asks my friend Carol Gaab? She tells a story in which she held up a water bottle and said agua and a few weeks later a student thought agua meant “bottle.” But here’s my point: If you hold up the bottle and say agua, and if you show a picture of a waterfall and say agua, and you show rain and say agua, and you show a glass of water and say agua, who’s not going to understand what the commonality is?

I believe translation is a faulty strategy for making up for the time problem.

Another strategy I can’t agree with that TPRS uses to ensure comprehension:

My choice: Balance comprehensibility and authenticity in speed.

This is TPRS’s biggest departure from first language acquisition. The method teaches that input has to be at least 90% comprehensible. To do that, TPRS trainers say translate targets, and then, go slow. Like really, really slow. One TPRS presenter told me we should imagine every word out of our mouths is a coin dropping into a well, and maybe then we’ll be speaking slowly enough.

The problem is that students constantly fed this type of language do not typically understand authentic language – because this type of language is far from authentic in any natural context at all. No one talks to children that way. No one talks to anyone that way.

I’ve been told I shouldn’t be using authentic resources with my novice students simply because they can’t understand 90% of it (and because I’m overestimating how much students can be engaged by Starbucks Mexico instead of being asked the same question 30 different ways in one class period).

All the success stories I’ve seen that counteract my claim here are about motivated, high-aptitude learners that aren’t representative of the larger group. I watched my “advanced” students struggle and fight to understand an authentic speaker tell their age because they never had to listen to authentic language before Spanish 3.

My choice: Ask for and expect output as a vital piece of the puzzle.

I confess I’ve had some rather difficult interactions on this particular point. I’m guessing few TPRS teachers would agree with the advocate who recently told me that output in the language classroom is irrelevant, but it is a core tenet of TPRS that “forcing output is not only not helpful, but can actually be harmful for students.” One teacher who recently asked my opinion on TPRS was baffled by this:

I personally love to ‘force output’ and have seen the fruits of those efforts so this seems a little too idealistic to me. I am all for CI and ‘lowering’ the affective filter, but what I love is pushing students to do things they thought they could not do. I know that I did not start really speaking Spanish until I started teaching and that was because the circumstances ‘forced my output.’ Therefore I love to recreate that ‘forcing of output’ environment.

Babies do not speak because they actually can’t. My toddler doesn’t say “My head hurts. Can I have some Tylenol?” because she is actually not capable of it. Physically, she doesn’t know what sounds will convey the meaning, or even how to make her mouth emit those sounds. This cannot be true with second language acquisition. Students are capable of output of some kind from the very beginning, so the “silent period” concept is very muddy. Very.

I agree that many teachers push their students too far too fast – you cannot reasonably expect students to manipulate past tenses accurately until they can consistently hit Advanced Low proficiency, which cannot be achieved in 2 years except by the most motivated and gifted students – but I do not agree that we can’t push them at all. One TPRS teacher’s argument was that output was just “motor memory,” as if that doesn’t matter, but we know it does. We’ve watched our students ace an essay and then fought to understand their stilted spoken output, because the motor memory really matters.

In trying to defend this point to me, Stephen Krashen argued his research. What was his research? He presented two case studies involving subjects who produced written language because they were disabled and physically incapable of speech. When I asked for research based on groups who could speak, he had no response.

I like some of Krashen’s theories. Quite honestly I’m a much better language teacher because of his writing shifted how I think about language learning. But I also highly respect Lightbown and Spada, Ellis, Swain, Gass, Selinker, Curtain, Doughty and Long– some tenets of TPRS ignore very smart people on the sidelines saying, “Wait a minute, perhaps it’s not quite so clear-cut as all that” in the name of “Krashen said this, Ray does this, Slavic does that.”

The TPRS defense on the output issue is that no, they don’t force students to produce language (the way I do when, for example, I do a speaking assessment and require interaction on Edmodo in the first unit of Spanish 1). But the TPRS students can, and do, when it comes naturally. But – I know, I’m a broken record – if I don’t have to wait until they do (and research says I don’t), and there’s not enough time for them all, then why would I?

The widespread phenomena of passive bilingualism and third-generation shift pose interesting questions here. In a nutshell, it’s the situation in which an immigrant’s child grows up hearing their parents’ native language and so they can understand it but they can’t speak it. Then, of course, their children are not bilingual at all. This is painfully real in my own life. My preschooler has to be forced to speak Spanish unless she has a lexical gap in English, because she says that “Spanish is too hard” and “I don’t like it” and “I can’t do it” (sound familiar?). We can claim social and cultural factors in play, but the fact is our students live in the same society that Zoe does.

Spontaneous accurate output may happen in your classroom today with a few students. We can believe all we want to that in a few years students will suddenly blossom into proficient speakers; it’s simply not supported.

My choice: Design curriculum to move through ACTFL proficiency standards, not simply high-frequency structures.

TPRS is often difficult to align with the ACTFL proficiency standards, claiming that learners “skip” the novice level (really, they skip around capable of benchmarks from some levels and miss others), and so, according to some, the standards are faulty and should be ignored.

But the ACTFL proficiency standards are not a fly-by-night set of descriptions put together by people who don’t know anything about language acquisition. They acknowledge that language capability is anything but random. Language learners, especially in the limited time we see them, and the age at which we see them, need to be able to accomplish certain things beginning with survival language and moving up to more advanced tasks, tasks based on communicating meaning.

Though they can be a measure for anyone, the purpose of proficiency standards is not to describe L1 acquisition; they describe L2 learning. The L2 process may somewhat (or largely) mirror the L1 process but -you guessed it- there isn’t enough time, so it benefits our students more to help them move through a sequence of desirable tasks in the L2. So what’s the result for TPRS? If the teacher ignores proficiency tasks, students end up with large holes in proficiency; they can describe an object, but can’t make plans to attend an event, for example.

That said, most prominent TPRS teacher-trainers acknowledge and respect the importance of the proficiency standards.

Don’t take it or leave it

As TPRS teacher/blogger “MJ” says,

I’m realizing that different parts of CI work in different situations, for different purposes, and with different sets of kids. I was trying to force Movie Talk and TPR and Scaffolding Literacy and TPRS stories and Embedded Reading into every lesson. The down side to pure TPRS is that it can’t work for everything, with every kid in every situation.

Anyone who used to think I’m smart is probably dumbfounded by how obvious that statement is, but I’m a slow learner. CI is king. TPRS was the tool by which I learned (and keep learning) to do CI. TPRS is magical at the beginning levels, but isn’t necessarily the only way to teach the beginning levels.

The main “con” for me is that “TPRS” puts off so many language teachers. I’m sad that people are offended before they even hear the rest of the story, or before asking questions about how TPRS teachers address reading, writing, speaking, or the biggest target, grammar…. people get offended just by the initials, then don’t hear that good TPRS teachers do include grammar (writing, reading, speaking) in their lessons, even if they don’t teach them to the same extent or in the same ways as teachers who use other methods.

Her concern isn’t unfounded. In a conversation I saw recently on Edmodo, a teacher (“Mrs. Johnson”) asked*,

I have a dilemma. In my Spanish class, I have a new student who comes to me from a TPRS Spanish class. I use Avancemos and we are finishing the sports unit and I gave her a quiz to see what level she’s in, and on the test her level is not that of my class. I don’t know what to do. Suggestions?

Naturally, someone wondered, well, is she “better” or “worse”?

Is it possible to move her to another class? Should she be in level 1 or 3?

Turns out the girl wasn’t up to par for Mrs. Johnson’s class, but she wasn’t thrilled about moving the student to another class:

She’s in level 1, grr… I wouldn’t like to move her…

So “Mrs. Straub” weighs in, frustrated with how poorly TPRS students supposedly do in grammar:

You’d better move her even if it’s a bother. In my experience the students who have studied with TPRS are dramatically lacking with verbs and grammar. Besides, the difference between level 1 and 2 can be a lot. I’m sorry.

The sentiment was somewhat more moderately echoed by “Mr. Frink” who, like I recommend here, incorporates TPRS into a mix (although probably not the mix I would choose):

I agree with Mrs. Straub. I use TPRS, but I also balance it with exercises with verbs and grammar. Everything’s better in moderation.

Perhaps you have the idea that you can take TPRS or leave it. I was told recently that if I’m not adhering to all the tenets of TPRS I cannot claim to use TPRS at all. Fine. I’ll just continue to call myself a storytelling teacher.

For what it’s worth, here’s the summary of my advice.

Don’t take TPRS.

Don’t leave TPRS.

Evaluate the practices of what TPRS preaches against what you know to be good language teaching principles, and against your situation, and against your personality, and take from TPRS what works for you, and leave the rest. And despite what a “this is the only thing that works and you better use all of it or you’re a failure” hard-core TPRS teacher may tell you, finding the blend that works for you is not only okay, it’s the best way.

For more advice

If you’re really interested in how you can integrate the best of TPRS into your situation, you could ask me and I’ll help you all I can. But honestly, you’ll probably get better help from some amazing teachers I count as friends and some of the best in the business. I’m sure they’d love to engage in a conversation with you and be professional, helpful, and not at all condescending about it.

*This conversation took place in Spanish; I’m translating here so anyone can benefit from the example.

NOTE: This post was heavily revised in January 2017 as part of my commitment to a more positive path.

For Carol Gaab’s comments on my arguments here, see her rebuttal guest post.

53 Comments

Comments are closed.

I can tell from the way you wrote this blog that it sounds like you’ve been feeling attacked for your teaching style, which is truly unfortunate. I know in older #langchat summaries that there has been discussion (and emphasis for the moderators) about being welcoming to teachers of differing teaching styles and not putting others down. As a true mutt-style teacher, I think there are a lot of equally valid ways to teach a foreign language. In the end, it comes down to ‘can the students use it or not?’ If they can, does it really matter how they got there?

That being said, you are definitely a driving force in the Spanish teaching community and you are an inspiration for teachers like myself. These last two posts echo a lot of my sentiments about TPRS (admittedly, I have no formal training with it) and I think you do a good job of laying out the pros and cons for teachers who might not be familiar with the style.

Thanks for the comment, Courtney. I do want to be clear that there are many great things TPRS has to offer the language teaching community. I wouldn’t be the teacher I am today without having been introduced to it and anyone who can attend a workshop on it will not regret it.

But, I also want to be clear that this didn’t come from a couple of recent conversations with two or three marginalized TPRS teachers. I had this post in draft mode for at least six months and it came from my six years of experiences with TPRS and the teachers who use the method and lots of other people. The most respected author in elementary language teaching described the method to me as shallow in culture and content and representing an “unthinking mentality.” A friend in ACTFL leadership recently described it as the “most teacher-centric method out there” with a “limited shelf life.” There’s sharp division in the field leadership over the issue, precisely because there are a lot of valid ways to approach language teaching, but we also know there are a lot of invalid ways. We need to be open to all the ways that will get our students there, as you say, but be wise to evaluate aspects that might slow down or even hinder the process. Hope that makes sense.

Great post! I love your insights. Your approach to language teaching has helped me (and my students). I “threw” out the textbook years ago and have slowly been developing a curriculum based on CI and authentic resources. I still need work on my storytelling and I have had a hard time breaking away from thematic vocabulary. I stumbled upon your website about 3 or 4 years ago, and have been paying close attention every since. Keep the insights and ideas coming.

I can’t thank you enough for these posts on TPRS, pro and con, and its relationship to proficiency guidelines. I have been using TPRS-style storytelling almost from the beginning, in combination with more communicative lessons and “survive the next Spanish teacher” grammar lessons. I agree with much of what you say about its pros and cons. I know that what I’m doing is not real TPRS to many people; usually I write the stories in order to control the vocabulary and ensure repeats of a grammar structure, for example, and I don’t use it exclusively. Instead it introduces, seasons, or enhances my units. The harder the grammar, the more I use TPRS or some simply chain story that students can build on (or not, as their abilities dictate. Everyone, however, is producing some language). Maybe I’m just not good enough at it to do pure TPRS but I also have real worries about output, along the same lines as you described, as well as the worry that some students learn far more than others. One thing I’ve learned recently is that in classes with serious behavior problems, TPRS is as big a challenge as a boon – for me, anyway. For some students, if the work isn’t written or recorded in some way, it’s not due. TPRS strikes them as a good time to take a nap. That said, I do think the far bigger injustice is the amount of Spanish being taught — you could practically put that word “taught” in quotes; better to say “covered” — with little or no input. It’s absolutely appalling to run into teacher after teacher who is frustrated with students’ inability to convert material they saw only on worksheets into spoken conversation. You may be so good at input and so surrounded by other good teachers that you don’t realize what a treasure it is to find a classroom with decent amounts of input. So, I’m grateful for what TPRS has taught me. If nothing else it has made the importance of input clear. But there are other ways to provide what is effectively input; structured communicative practice is one. If a student asks 25 fellow students whether they like to eat Snickers, for example, everyone is hearing the structure “I like” many, many times….AND getting used to saying it. Thanks for putting TPRS into more context. I know this discussion will help me a lot.

AMEN! Best ten minutes of my day was spent reading this! Thanks for your insightful, well-thought, and justified response. I often am baffled my how some “true” TPRSers truly believe that no output is good, or that one can acquire L2 the same as L1 and their ONLY response when asked ‘How do you know this to be true?’ is that of Krashen’s “research”. My argument has always been that of myself growing up with parents who spoke Spanish but not being able to communicate AT ALL with them. It just doesn’t add up. Thanks for the sources of research, too. I can tell you spent a lot of time with this and I appreciate reading it.

Christina, even true tprs teachers feel that output is important. They just don’t believe that the language is introduced by students producing (and then forgetting). Krashen does not even believe that so it makes no sense that any tprs teacher would quote him. If this is how you think about true TPRS teachers, you may have encountered a few who have not been properly trained. There are people in every profession who are not properly trained and they should not be the example for the many who are using it successfully. I’m also a little baffled by you growing up with your parents speaking Spanish. Did they just speak to each other and not to you? That might explain why you didn’t learn Spanish from them.

I totally agree with you. I love some parts of TPRS, but the year we decided to go whole hog, our students fell behind. Once these students reached AP they were really behind. I had the worst AP scores ever. And I usually have really high scores. There just isn’t enough time. Read an essay from an AP practice. Not just 2,000 common words. Listen to the AP exam. Wow did they really just speak that fast? Yep. It also produces apathetic learners (lazy, if you will). Once they are asked to produce, they resist. What? I’ve just been listening and reading from grades 1 – 6. Now I actually have to work at this? That means that the upper level teachers get a lot of push back. We also get a lot of push back about the pace of the class. Ugh. I feel your pain.

Kimberly, there are many teachers who use tprs who have great AP scores – even after only 3 – 4 years of language instruction when this could not be accomplished (or accomplished with only a few students) by any other method. You should go to the pro-TPRS websites and find out from these teachers what they are doing to have such incredible pass rates and high scores. In upper levels using tprs, there is a lot of grammar instruction and much more output.

Thanks for your interaction here, Mary. I want to respond to be clear that I am not an anti-TPRS website and visitors should be sure to check out the companion posts to this one, my “What I love about TPRS” entry and my friend Carol Gaab’s counterpoint to this post. I simply encourage all teachers to not jump on one bandwagon or another without using sound methodological principles to evaluate particular methods, and to consider a point of view that the answers are very rarely in one “camp” or another but rather somewhere in a salad mix of many.

This was an interesting read to be sure. While I don’t suscribe to the TPRS model of teaching, I feel that engaging the student in role playing in order to help acquire the language is important. With that said, I am going to a workshop put on by OWL, whom I saw at the NHAWLTS conference and was intrigued. One of the things I do with my students now is I introduce new words while I’m doing my intro dialogue. Words I know they have not heard before I spell on the board. This helps them visualize, understand the pronunciation and perhaps even intuit the meaning. I find when I do this, they are quicker to grasp the word. Also, repetition,repetition,repetition. As always, thanks for your postings.

http://www.owlanguage.com/

Anyone who can get to a TPRS workshop will not regret it – they’ll come away with some great ideas to make input comprehensible and memorable for students! Thanks for the comments as always Loly.

These posts are great! I agree with a lot of what you wrote. One of the biggest problems that I had is even after attending sessions and a conference, I do not feel comfortable in the method. I need to change things up sooner rather than later. I love using TPRS novels and different methods while still teaching in a more “traditional” style as well.

I’m a proponent of a long silent period and I fall inline much more with Ben Slavic mentioned above, in that I never think of a list of words before a lesson or make any attempt to cover words at premeditated interval. You mentioned multiple times that TPRS takes a long time. I’ve never been concerned with how long the method takes, just that the end results are worth the effort.

Since I’ve never taught in the US I’m not sure what standards of measure are required of your teaching. I wonder if you’ve written about this, or would care to? How best to fit TPRS into the standard curriculum? Or maybe the pitfalls of using TPRS in the classroom?

My concern with the length is that if we can get results that are worth the effort in multiple ways, why wouldn’t we choose ways that speed up the process?

Standards in schools and curriculum are very different from setting to setting. I know teachers who have successfully incorporated TCI principles into a curriculum they were required to teach. Personally, I have almost no requirements.

[…] This guest post is a response to last week’s “What I hate about TPRS.” […]

I find your comments on patterning puzzling. Frankly, I would’ve expected the complaint to go in the other direction, saying that TPRS has too formal a pattern. Ben may be an example of someone who likes to play fast and loose with the structures, but I’d consider him more of an outlier in that regard than the standard. Most commonly, TPRS is considered to advocate picking a few structures to focus on, and getting lots of repetition on those structures. This goes along with the idea of making a 3-part story, to give it structure, a predictable pattern, and more opportunity for repetition of the structures.

You mention ignoring meta-cognitive awareness, though I think Carol’s rebuttal is pretty clear on the use of pop-ups, which factor directly into mega-cognitive awareness. Maybe the fact that pop-ups weren’t an original tenet of TPRS is the source of the confusion, but I’d say it’s pretty widely accepted now.

In the area of translation, we differ slightly in opinion. Honestly, it’s kind of funny to me that this article advocates accepting and utilizing learners’ metacognitive awareness, but rejects establishing meaning through the L1. Is that not just another example of using what the learner already has, that is, an L1? And my familiarity with the research is that there is a somewhat predictable progression from initially linking L2 to the L1, which with increasing proficiency transitions to linking L2 to the concept. But that initial L2-L1 link is pretty unavoidable, even if the teacher doesn’t “translate.” Do we think that drawing a picture of a butterfly somehow keeps a student from thinking in his head: butterfly (if he thinks of it accurately at all)? The only difference I see between letting the kid read the L1 word and confirm the meaning, and drawing a picture/doing an interpretive dance and letting the kid “say” the word in his head (because, c’mon, he totally will), is that the latter opens up lots of possible misinterpretations.

It’s so fascinating to hear how different people interpret the same input. This applies to language learning, of course, but I’m specifically referring to what people take away from learning a method. And there are lots of people who get a little drunk on the TPRS and might start to speak too unequivocally about the “best” and “only” way to do things. But that’s a person’s interpretation (maybe a slightly too enthusiastic person), not the heart of the method, and this is “what we hate/love about TPRS” not “some individual TPRS practitioners”

Thanks for your comment, Lake. I don’t consider the few structures you’re talking about as the targets repeated in a TPRS lesson, at least the way I’ve seen them, as patterning. I’m talking about a lesson specifically designed to get students to extract an indirect object pronoun pattern, for example, in phrases like “I like, he likes, he doesn’t care, I don’t care.” What I’ve seen is more like a story full of random CI with the targets of “went to town,” “falls all the time,” and “up in a tree.” As for translation, I reject establishing meaning through the L1 because it encourages students to link meaning to the L1. I know it will happen, but I’m not going to encourage it. I’m going to do everything I can to discourage it, which includes establishing meaning in other ways, if I can, and checking for confusion on meaning (which, incidentally, gets students more repetitions and more CI in the L2, which is our goal anyway).

But ‘doing everything you can to discourage it’ runs counter to scientific evidence. When you learn an L2, it’s first housed in the same location in your brain as your L1. It doesn’t separate from this common location until a higher level of proficiency is attained. I learned this way before I knew about TPRS when I was a Linguistics major read research from class from Linguistics and neuroscience. Forgive me for not searching for a link to post, but, albeit it anecdote-ally, my personal experience coincides with this phenomenon. Linked with the aforementioned brain research, is the idea that speaking a language involves actually suppressing the neural network of another in your brain (man there’s some cool stuff out there on that). When I was studying German after I had already learned Chinese, Chinese was always coming up in my mind and ‘getting in the way’ of my German when I had to practice with a partner. Presumable, because my German was going to the same place my Chinese was already housed in.

At least for the first 1 to 2 years, using the L1 is just a time saver and helps clarify the distinctions between some terms. Later, you could always switch to all L2, perhaps.

I used to teach ESL and we had to create our own materials, always. Those first three years nearly killed me as I only sleep 3~4 hours a night preparing so much to get the meaning across to my students of various native tongues. It’s a godsend not to have to spend so much time preparing pictures, drawing, and videos just to establish what something meant. It’s also considered a best practice to have students look up targeted words in a bilingual dictionary as a way to establish early meaning and ‘activate prior knowledge.’

I feel the same way as Dr. Waltz does on her blog post linked below about the “mythical wall” http://terrywaltz.com/comprehensible-input-blog/the-mythical-wall/

Thanks for your comments, Ryan. We’re disagreeing on the usefulness of using English for a very important reason – the research isn’t clear cut. We can’t say “this is what happens in the brain when you learn an L2” – no researcher is willing to say that. The best anyone can do is to say, here’s the evidence, and here’s a model that may explain it. The ways these models try to explain phenomena sometimes completely, sometimes partially, contradict each other. What I can offer is that there are robust bodies of research showing that the more time students spend in mostly comprehensible L2, the more proficient they become (which aligns with most of TPRS), and that motivation, noticing, and a host of other factors are also heavily involved. Krashen wants us to believe that input is the only factor. It’s simply untrue. Some TPRS practitioners preach just put it in English all the time, who cares, but my argument is, we very obviously do not always have to do it, though sometimes it’s a great time-saver. I simply mean it’s not an all-or-nothing thing. English does have its place in the classroom. Translating all the vocabulary is not it.

You might also enjoy looking into the research on codeswitching, with your interest in neurolinguistics, if you haven’t already.

–Sara-Elizabeth

I would like to add on to your reasoning for drawing something on the board or talking around the language. I don’t just do it to try to keep my students’ heads in French. I also do it to set an example for my student. I don’t want my students to develop the habit of just throwing out an English word when they don’t know how to express something in the TL. It’s a bad habit for the classroom, and it won’t work if they’re abroad. I believe that if my students see my effort and patience in communicating without English that it will instill in them the patience to work around the language without switching into English to try to communicate.

[…] may have seen the example I used in my post What I hate about TPRS. One teacher has a student who has come from a TPRS class and can’t handle the coursework. […]

[…] magic was starting to wear off, so I switched to something new. Then, Carol posted this rebuttal to a fantastic Musicuentos post, and I was intrigued: is there a side to TPRS that I’m missing? Do others feel the same as I […]

[…] What I Hate about TPRS – One teacher’s honest disagreement with CI/TPRS, especially about delaying student output/production until they are ready and not teaching explicit grammar. […]

[…] I first started investigating TPRS as a teaching method, a lot of things clicked with me (and some didn’t) but one of the tips that made the most sense was that it didn’t make sense to teach past […]

[…] mind – how can we possibly replicate language acquisition in the classroom when we don’t have the time? – and answered, well, that he didn’t have an answer. Then, he wrapped up his […]

Thank you very much for this post and the previous one about what you see as the pros and con’s of TPRS! One of the most helpful things I’ve read in terms of processing TPRS methods and whether/how to incorporate them into my teaching. Thanks!

As always, I really appreciate your convictions, which you spelled out very clearly on both “sides”…

I just completed my first TPRS workshop this week with Blaine. I loved every second of it and was amazed at the German I learned in those two days!! 🙂 I am anxious to try some storytelling. But, one of the first things that struck me about the method was the teacher-centric approach as well as the lack of alignment to the ACTFL standards (which after 18 years of teaching, I am still trying to wrap my brain around properly!). After the workshop, I was feeling a little drunk on the TPRS KoolAid. Reading your thoughts helped calm me down a little. I have always believed in a mixed “bag of tricks” in terms of teaching, though in retrospect, I really have been much more of a traditionalist. I am spreading my wings now and with the help of great bloggers like yourself, the #langchat community, the OPI training I did last summer, and some wonderful collaboration in my township and district, I think I am headed in the right direction. I must say it is totally a difficult pill to swallow when you realize you’ve kinda sorta been doing it all wrong. But I am just glad to be aware and also to realize so many great educators out there have been down the same road as me.

I think I caught a picture of you and Blaine, Pam- great pic! “Drunk on the TPRS KoolAid” is a great way to describe it – we are primed to learn language and it’s super impressive in the small quantities in a workshop. It’s also super impressive as a tool in the classroom in the long-term but it’s a whole lot more complicated than it looks to get there! Enjoy your adventures in storytelling – I don’t think you will find as engaging a way anywhere to deliver comprehensible input to foster real student communication!

I don’t even know where to begin! We are thinking of trying a story with our 6th graders sooner than later. I know I am way more in my comfort zone teaching about verb forms and grammar and all that jazz, but knowing it is not impacting my students in a way that helps them become more proficient…well…let’s just say “I’m over it!”…haven’ t shown 6th graders a verb chart yet this year! (And coincidentally, they seem to have a decent handle on things like Soy/Eres/Es, Tengo/Tienes/Tiene, Me llamo/Te llamas/Se llama, etc!)

Have fun watching the magic! Let me know if I can help.

I am a professional translator and interpreter who also taught Spanish for adult leaners at the community college level for over 10 years. The community college sent me to a TPRS training several years ago. Although it was a small sample size, I was somewhat shocked that neither the Spanish teachers who attended the workshop nor the presenter were very proficient themselves. My impression was that TPRS would not be a serious language learning method for adults or adolescents with a reasonable level of sophistication. Furthermore, I have never met a serious language professional who acquired their skills through TPRS. I can see how TPRS could be quite engaging for children perhaps through middle school. In my opinion, it’s usefulness pretty much ends there.

My daughter is now in her third year of high school Spanish and is fed a steady diet of TPRS. Although she gets excellent grades in the courses, her knowledge of Spanish vocabulary and grammar is very low. I am very concerned about the proliferation an popularity of TPRS. I think that it is anti-intellectual rubbish. Foreign language acquisition is neither easy nor fast. We need to stop looking for a magic bullet that’s easy on the kids and easy on the teachers. TPRS makes me even more suspicious of pedagogical fads. A passionate, knowledgable instructor with excellent communication skills remains the foundation of effective teaching.

Thanks for your contribution, Mitch – a voice of experience is always helpful insight. I had not thought about this, but I don’t know a language professional who acquired their skills through TPRS either, and I’m friends with a LOT of TPRS teachers/trainers.

Three years ago my department chair decided to change to TPRS and I was forced to follow suite. While I was not particularly happy with the change, I did realize that since TPRS is so radically different from the “traditional” method (whatever that is), we would all have to go along to make it work. Thus, with 6 years to go before retirement, I began to reinvent myself. I do not regret it and would never go back to an approach based on copious amounts of grammar, huge lists of memorized vocabulary and undecipherable readings.

However I have reservations which have led me to stray from using TPRS in the “correct” way.

Grammar!! I’m lost here. Most of my students do not simply pick up the grammar from the readings and class activities. Pop up grammar often is not enough but too much grammar confuses my students. What’s the happy medium?

Output IS necessary. We learners of a foreign language know that speaking and writing correctly serve to reinforce our knowledge and help us become more effective communicators in the L2. Thus I push and help my students produce output that is correct because this correct output helps reinforce the language they have acquired and in turn serves as input for their classmates.

Our district does not offer Spanish in middle school so when we start TPRS in high school we are dealing with students with relatively high cognitive abilities. Therefore the TPRS stories that come with Carol Gaab’s book are way too childish and, in my opinion, almost insulting to my students.

This leads me to my greatest concern with TPRS, and this mirrors Mitch Wilson’s criticism. The simplicity and end goal of TPRS seems to remove the study of a foreign language from the list of serious “academic” subjects. This is where I really go “wrong” in the way I teach TPRS.

I have a back round in Spanish and Latin American literature and I use this back round to produce readings for my students. These readings, some of which are simplified short stories from authentic authors, use the vocabulary expressions from Gaab’s book but at the same time have a certain value as literature thus returning, in a minor way, “academic” status to the study of a foreign language. My students now have to think, reflect, infer and interpret not only the author’s words but also the meaning and or purpose of the story.

One final thought. It’s good that we foreign language teachers are constantly searching for a better way to teach our subject but believing we are going to find a magical method of teaching that enables our students to communicate effectively with native speakers after of 4 – 6 years (1100 hours of instruction) is ludicrous. This simply IS NOT going to happen. Acquiring a second language is a long and sometimes tedious adventure. There is NO MAGICAL FORMULA. All we teachers can really do is expose our students to a foreign language and hope they decide to pursue the adventure.

Thanks so much for your thoughts, Maicito. Much of what you said mirrors what I wrote recently in the post “The M that trumps your method, materials, and madness.”

Here’s a 2nd year story using Carol Gaab’s Vocabulary expression from Chapter 7 Minicuento A. Simple, yet treats a serious subject.

El extraterrestre

Todos los días María pasea por las calles (streets) de la ciudad. Un día, mientras pasea, María ve a un joven (young man) de aspecto muy raro. El joven tiene dos cabezas y cuatro piernas. María, que es una muchacha muy curiosa, y por eso siempre quiere conocer a personas y cosas (things) diferentes, decide hablar con el joven.

–Hola –le dice María al joven de aspecto raro–, ¿cómo te llamas?

–Me llamo Gzetbehks –responde el joven.

–¿Por qué tienes un nombre tan raro?

–Porque soy un extraterrestre del planeta, Duacabycuadrypye.

–Y, ¿por qué estás en mi planeta?

–Porque me gusta pasear por las galaxias y conocer los hábitos de las personas que viven en diferentes planetas. Además (Besides) busco una persona curiosa y aventurera que quiera pasear en mi nave espacial (space ship) y conocer otras galaxias conmigo.

–¡Yo soy una persona curiosa! –grita María–. Me gustan las aventuras y quiero conocer otras galaxias. ¿Puedo pasear contigo?

–Sí –contesta Gzetbehks–, puedes pasear conmigo. Juntos (together) conoceremos muchas galaxias nuevas.

Al entrar en la nave espacial de Gzetbehks María tiene un poco de miedo porque la nave tiene un aspecto raro y porque ella piensa (thinks) que es posible que Gzetbehks la maltrate. Pero Gzetbehks es un extraterrestre bueno y simpático y trata muy bien a María. Los jóvenes salen muy contentos del sistema solar y empiezan a pasean por las galaxias. Mientras pasean, ellos hablan de sus planetas, de sus familias y de sus vidas. Durante estas conversaciones íntimas María y Gzetbehks se conocen muy bien y pronto se enamoran. Un día Gzetbehks le pregunta a María:

–¿Te casas conmigo?

María acepta casarse con su novio extraterrestre y ahora ella y su esposo viven muy enamorados en Duacabycuadrypye, el planeta natal (native) de Gzetbehks. Pero hay un problema. Muchos de los habitantes de Duacabycuadrypye piensan (think) que María tiene un aspecto muy raro y por eso siempre la maltratan. Es que (You see) María es del planeta Trycepsyxpydos y los habitantes de ese planeta tienen tres cabezas y seis piernas.

Hopefully I haven’t overstepped the rules of this blog by posting this.

Thanks for the example!

[…] blogger Sara Cottrell writes about what she doesn’t like about T.P.R.S. here. http://musicuentos.com/2014/02/tprs2/ , to which Carol Gaab responds here […]

[…] of PQA, I find myself in the same camp that Sara-Elizabeth was in last year in her “what I hate about TPRS” post. I also agree with what she says in its partner post, “what I love about […]

Love this post. I agree and have been shamed by another language teacher for not adhering strictly to TPRS practices. Parts of it do work best in different situations. One of the elemts of the L1 process we cannot reproduce is the fact that a 2 year old’s brain is not necessarily wired to find patterns to make their acquisition adventure easier the way in which an adolescent’s is. (This is partially what is alluded to when talking about the critical window). This means that while teaching grammar to a toddler would be a waste of time, ignoring it completely with an adolescent student would be doing them a disservice. That’s of course, not to advocate teaching Spanish or French the way we were taught in the 80’s either. All it takes is having a kid to know that being patient for output won’t work. Is it any wonder why that colleague who admonished me for not being a struct TPRS adherent had no children?

Again, thanks for the insightful post.

Thanks for your comment, Todd!

[…] re: teaching, learning, language acquisition, and assessment. I like some of its tenets, but, some of them leave big questions in my mind. That’s […]

What a great article; thank you for sharing. I stumbled upon this after doing a google search for “TPRS in the elementary classroom”. I have watched TPRS in middle & high school levels, and it sure looks like fun, but I often find myself thinking, when do these kids really learn Spanish (or French)? Moreover, I know that my younger students, even my 5th graders, would have difficulty sitting through 30 minutes of TPRS every time they come to class. Bravo to you for voicing alternative thoughts in this huge wave of TPRS-ism.

Thanks for your comments, Amy! I think the biggest problem is in teachers thinking they need or even should fill a 30-60 minute class period with TPRS, rather than seeing it as a potentially very useful tool in the vast array of ways to provide comprehensible input and meaningful interaction. So let’s get to that, right? 🙂

I merely wanted to say that you are spot -on with many of your criticisms of TPRS. Over the holidays I have closely followed some of the Ci/TPRS facebook pages and have become disappointed by members’ reactions to my having raised similar issues to them. Now that “story listening” seems to be a favourite of many, teachers are claiming that this is the purest form of CI, and that – as research supposedly shows – follow-up activities, namely those higher on Bloom’s taxonomy, are of little benefit.

I embrace – deeply – certain aspects of what is generally seen as TPRS, but am terribly disappointed when my colleagues so readily dispose of other aspects of SLA.

Personally, I am hard-pressed to “ooh” and “aah” when a teacher tells me the pencil is indeed yellow, and by no means will have the desire to follow such a story, with its circling, for the better part of the instruction hour.

Why, I wonder, do strong proponents of CI / Story listening / OWI / TPRS so eagerly dismiss other aspects of SLA that could buttress their own work? It seems that the strongest advocates are myopic in doing this. In bringing this up, I feel that others are reacting as if the very tenets of a personal religion are being undermined.

Strong adherents of TPRS have “claimed victory” in “solidly refuting” each of your criticisms, something which has not persuaded me, as I consider your points extremely valid and not to be dismissed. How can one NOT embrace metacognitive learning strategies and giving students feedback on their work?

Thank you – for this balance.

Thanks so much for stopping by with another balanced view, Joe, and thanks for the genuine laugh about the “ooh” over a yellow pencil. I have appreciated this year seeing what I see as a separation among teachers and presenters who are so focused on “refuting” and are married to the method as if it were the only one, and defend it as if it were a marriage, and the brilliant teachers and presenters who have had such positive results using TPRS as one of their main strategies among many. I’ve seen the latter leave Facebook groups and Twitter conversations that were pulling the conversation down into almost the mire of politics. I want to be a teacher with my eyes open to any effective strategy! I highly recommend Steve Smith’s blog

for more of a balanced view.

Best,

Sara-Elizabeth

I find a combination of different teaching approaches helpful. Students have different learning styles and so the teaching style needs to be flexible and adjustable according to the students. I was a ESL teacher first then a Chinese teacher. Chinese and English have only 2% similarity and it needs to taught in a way that students feel comfortable not overwhelming.

Thanks for this post. I am in the process of moving proficiency based, and I have been bouncing back and forth between hard core TPRS folks and those that push authres. It is truly confusing. I think your opinion has been the most reasonable one I have heard so far, so I will hold off purchasing expensive sets of TPRS novels for my classes! Mil gracias

Is now the right time to tell you that last year we did Brandon Brown vs. Yucatán and Tumba and this year we’ll do Fiesta fatal and Robo en la noche? 😉 There’s a use for any good tool – just not a narrow vision that there’s only one good tool, in my opinion!

TOP 3 2017

Thanks a million for this post, because I really respect your work and also someone whose work you strongly disagreed with in the original version, and when I read the original version (during the 2015 IFLT conference) I experienced a tremendous cognitive dissonance that made me want to give up (like seeing your pedagogical parents in conflict–if the best of the best can’t agree, how do the rest of us figure out what to do?). This new post gives me a lot more peace and direction about how to synthesize approaches. Thank you!!

THANK YOU for adding to this conversation, Kristi!

Thank you so much for your measured article. One of the things I find difficult about the TPRS vs. Other Methods argument is that people are either in one camp or the other and it is difficult to find unbiased research (“I have always been a TPRS teacher and I love it” or “I have never used TPRS but I know it’s bad”).

I am an AP teacher at a school where we have always used mixed-methods in the past. We recently hired a new teacher who only uses TPRS and CI and it has been a very difficult transition for all of us since a true TPRS teacher doesn’t value what we have been doing at our school for years. In the past, our school has had VERY high pass rates for the AP Language and Culture exam due to this mixed method and she just can’t get on board. I don’t want to her throw away all of her TPRS methods but I am so stressed out by the low level of reading and listening of her Level 3 students who are about to be my AP class!

Also, I don’t know what TPRS has to say about native-speakers but they are incredibly bored in her class by all the call-and-response/CI readings. Is TPRS always an appropriate method even if you have a class of 1/2 native-speakers (both active and passive bilinguals)?

I see her methods working very well for Level 1 and younger students but not well for Level 3 or older students…

Thanks for stopping by, Savannah!

It sounds like the teacher is stuck on TPRS as the only set of strategies that are CI. Comprehensible input is essential for language acquisition at any stage, of course, but even among TPRS teachers this can look very different at different stages. I recommend you suggest that she investigate Carrie Toth’s blog, Somewhere to Share. Carrie is well-known and deservedly well-respected among all TCI teachers, but she teaches upper levels in a very effective, challenging way. Mike Peto also has a lot to offer on the topic of using TCI strategies with heritage speakers. (Just Google his name.) Best wishes for peace and progress and proficiency!